Descent into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

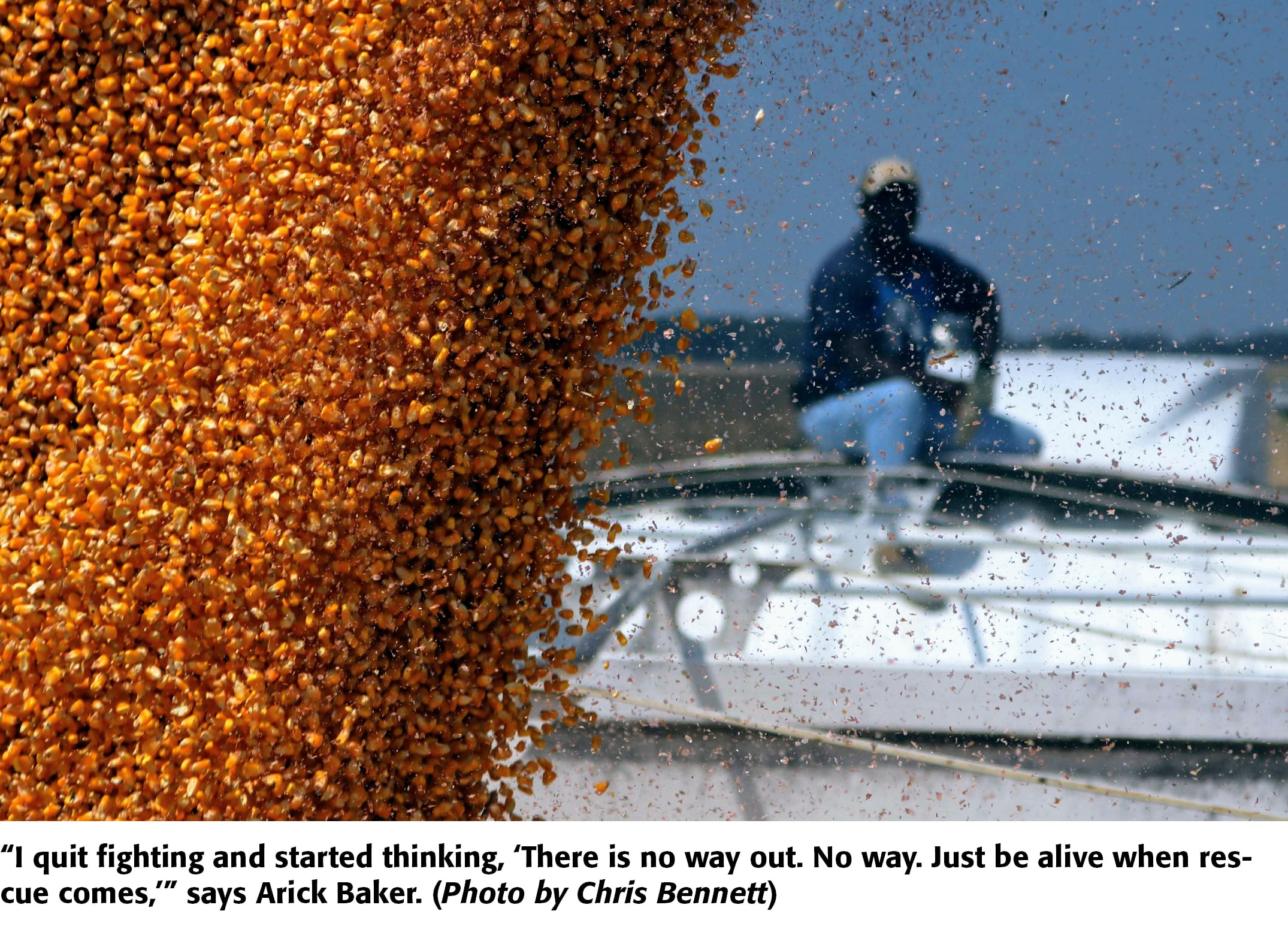

Deep in the pocket of the Midwest, and deeper still in the belly of an Iowa grain bin, Arick Baker was a dead man in a corn tomb. Buried in claustrophobic terror, Baker was fastened in place by the grip of 2 billion kernels pushing in concert against his body. Still as a statue in pitch black silence—splayed limbs extending at varying angles into the grain—he was a falling man frozen in motion. No light, no sound and near total sensory deprivation beneath the corn, save for the agony of 24,000 bushels driving into his skin at hundreds of pounds of pressure per square inch. Enough. Baker stopped fighting, held his breath and waited for death. What the grain gets, the grain keeps.

Deep in the pocket of the Midwest, and deeper still in the belly of an Iowa grain bin, Arick Baker was a dead man in a corn tomb. Buried in claustrophobic terror, Baker was fastened in place by the grip of 2 billion kernels pushing in concert against his body. Still as a statue in pitch black silence—splayed limbs extending at varying angles into the grain—he was a falling man frozen in motion. No light, no sound and near total sensory deprivation beneath the corn, save for the agony of 24,000 bushels driving into his skin at hundreds of pounds of pressure per square inch. Enough. Baker stopped fighting, held his breath and waited for death. What the grain gets, the grain keeps.

Machinery, harvest chaos and long hours are a ready-made recipe for consistent hazards in agriculture. However, the trip from tractors and combines to coffins often detours at the grain bin. Soybeans and wheat claim a share of farmer lives, but corn is the unforgiving king of reapers, luring in victims with the fluidity of quicksand, and sealing escape with the unbreakable grip of hardened cement. When a corn wall crashes, or a corn bridge collapses, there is no escape for a hasty farmer—young or old. Yet, when Arick Baker of Iowa and Buddy Schumacher of Wisconsin tumbled into corn flows and emerged to tell harrowing tales separated by three years and 250 miles, the rookie and the veteran became rare, remarkable exceptions that prove the rule.

Iowa: Gone in 60 Seconds

In 2013, Baker, then a spry 23-year-old, farmed corn and soybeans alongside his father, Rick, on 1,300 acres, in addition to custom work on a separate 1,100 acres. On Wednesday, June 26, Baker woke at 7 a.m., in the small central Iowa town of Eldora (pop. 2,600), roughly 80 miles northeast of Des Moines, on a steaming summer day bound for a 92 F high.

Respecting a heat index forecast at 100+ F, he threw on a sleeveless t-shirt and canvas shorts, laced up steel-toe Caterpillar boots, and jumped into a 2011 Silverado 1500, bound for his operation without the slightest premonition of the hell before him. As Baker drove past field after field split by gravel roads across what is arguably God’s country of U.S. agriculture and home to some of the highest farmland values in the nation, he took little notice of an object bouncing in the passenger seat—a plastic respiratory mask. Less than a year earlier, leaving a national farm show with pockets full and hands empty, Baker spotted the mask on a booth table near the venue exit. It was a hard hat with a clear face guard and a snug elastic neck covering. Despite no asthma or dust allergies, Baker slapped down $379 to cover the price tag and walked away with a life-altering purchase.

Arriving at the family farm bins, Baker began helping Rick and co-worker Kay Palmer load trucks and haul corn to an elevator 45 minutes west in Hamilton County. For two days prior, the trio had targeted a 60,000 bu. bin (48’ diameter) and after several auger hitches, emptied it just below the halfway level. (At the previous fall harvest in 2012, unusually heavy rains equated to wet grain, higher than ideal storage moisture, and the strong potential for corn clumping in the bin.) After repeated auger clogs, Baker climbed into the bin and went over the top to dislodge crusted corn on both Monday and Tuesday. During the second load Wednesday morning, clumping again hindered the hauling process. At approximately 10 a.m., Baker started up the near 60’-high bin staircase, his boots clanking on the 72 winding steps as he slipped on the respiratory mask and walked past a bold warning sign fastened to the galvanized steel: Do Not Enter Bin While Grain Is Being Loaded or Unloaded. Auger running, he accessed the rooftop hatch, picked up a probe, and climbed down an inner ladder into stifling 137 F heat with a 3/8” tow rope looped over his shoulder and tied to an upper rung, his descent echoing through the half-light over the sea of corn.

Grasping the probe, an 8’ PVC pipe with a 1” diameter, Baker took his 6’ 2”, 200 lb. frame and stepped into the corn, sinking just below his calves. He could feel the tingle of the auger in his feet, a light vibration that ran up his legs as he moved to the bin’s center and jabbed the probe into the corn. Far below, approximately 18” above the bin floor, a hidden, crusted corn shelf arced across an empty pocket. Baker was dead center above the void, standing on a high-wire, unknowingly destroying the shelf with each thrust of the probe.

Up above, in the hatch window, Rick’s face was outlined against a bright morning sky, peering down as Baker loosened the clogs. Shifting his gaze from Baker to the semi-trailer on the ground, Rick watched as the vehicle approached loading capacity. He whistled down to signal Baker and began descending the staircase in order to shut off the auger and transport the trailer to Hamilton County. As Rick made his exit, Baker tightened his grip on the PVC probe and made a final thrust into the corn. One last poke.

In an instant, the shelf broke and Baker rocketed downward into the corn, jerked by an unseen hand. Immediately, the collapse covered Baker to his waist in corn and swarmed up his torso as he clawed and writhed in the flow. A prisoner of physics, he was sinking in a funnel as surely as if swallowed by the corn. Primal panic. Abject terror. “I had no time to think, no time for anything but instinct. I was screaming for my dad and fighting for my life. Fifteen seconds later I looked around one more time and grabbed the rope on my shoulder with my hand before I went completely under the corn. That’s it; I was gone that fast.”

Submerged in the grain, Baker continued to descend and felt a telltale vibration run through his body. He was headed for Archimedes’ giant metal screw: The auger was still running.

Wisconsin: “Why Can’t You Get Out?”

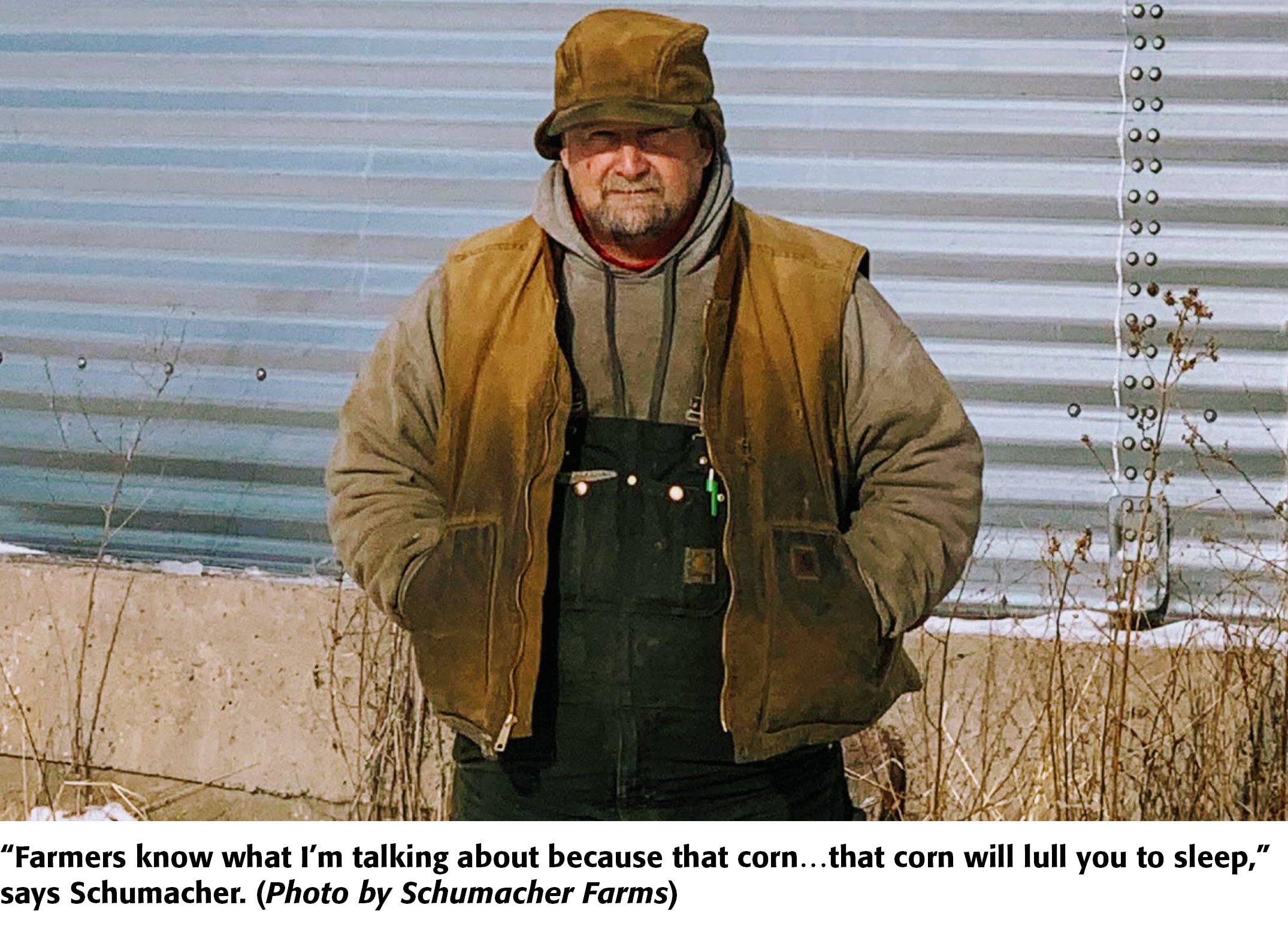

Buddy Schumacher barely noticed the cold a few degrees above freezing on a winter day in western Wisconsin in 2010. He slid his cellphone into the chest pocket of insulated Carhartt overalls and looked up at a 49,000 bu. grain bin perched on his St. Croix County farmland. With a 580-head calf ranch alongside 1,000 acres of corn and soybeans, 2009 had been a messy year filled with harvest ruts and wet crops. The previous fall’s heavy rains were biting again on a Jan. 22 afternoon, as the moisture aftereffects slowed bin unloading to a crawl.

At 2 p.m., with the bin half-full and the auger turned off, Schumacher, 52, climbed the staircase and slid his 5’6”, 200-lb. body through the rooftop access and onto the inner ladder—alone with no harness or even a rope. “Everything at that point was ordinary,” Schumacher recalls. “I could hear my echoes like I was surrounded by a giant tin can. I had done this before when I needed to, and I was dealing with the crust of a poor-conditioned crop.”

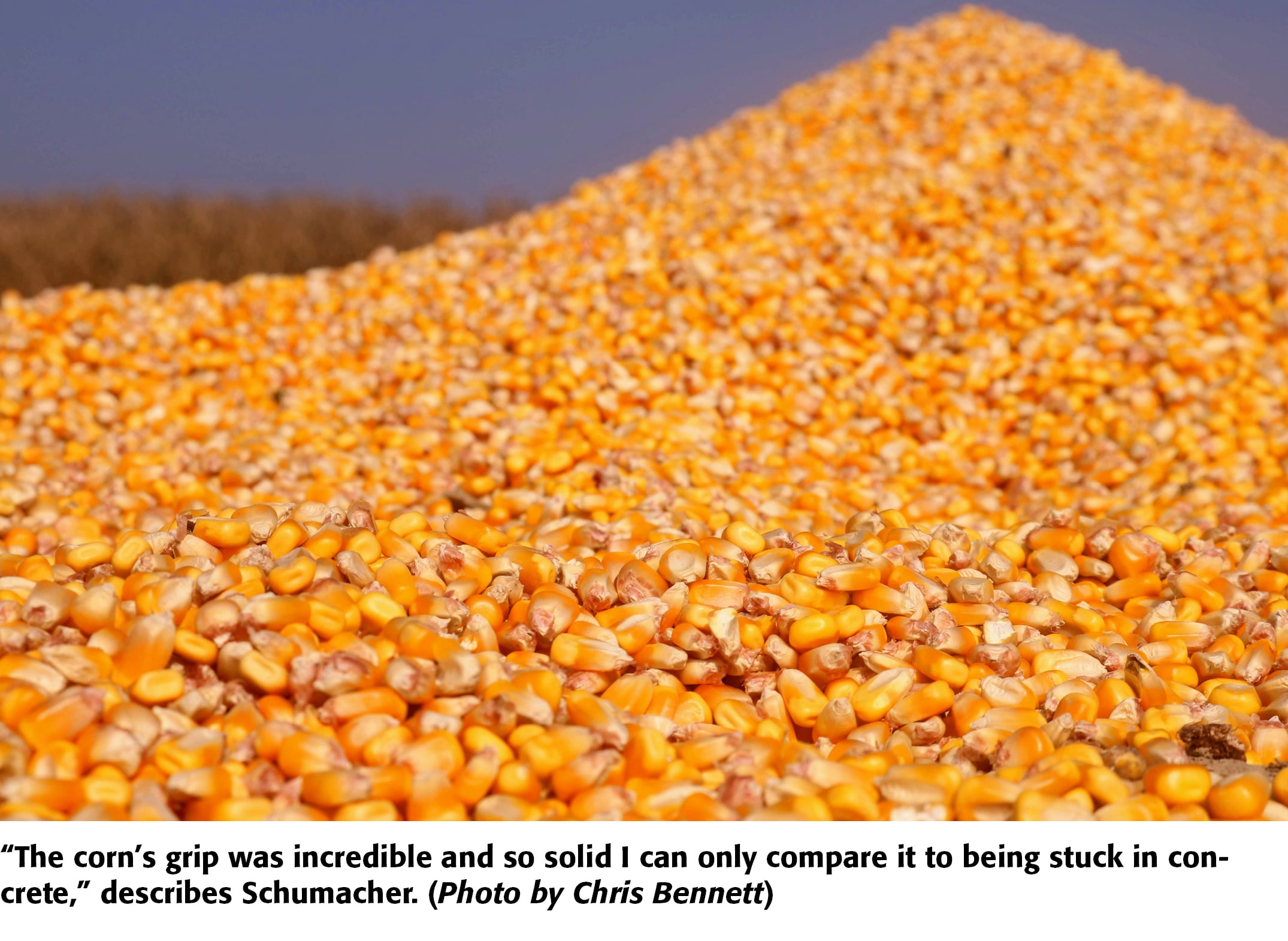

Schumacher stepped into the corn and started across the surface, sinking roughly 10” with each stride. Fifteen steps later, he was dead-center of the bin, armed with a 10’ by 2” PVC pipe. From Schumacher’s perspective, he was atop a shifting, but solid mass. In reality, he was standing over a crusted corn bridge, and as he lifted the pipe to drive downward, the section broke and Schumacher shot into the grain. “I got zero warning and it happened in a flash. It was so fast it’s hard to even remember. I tried to stick the pole out sideways and there was no effect. I went right down to my armpits and upper chest. Every time I wiggled, the corn got tighter. The corn’s grip was incredible and so solid I can only compare it to being stuck in concrete.”

With each exhalation of breath, the corn squeezed tighter against Schumacher’s chest. He held his nerve and reached for the phone in his bib pocket. Twenty miles away, Clint Schumacher was finishing a day of dairy work when his cell rang. “I was walking away from work when dad called. I let it ring and decided to call him back from the truck.”

Minutes later, behind the wheel of a 2004 Chevrolet ¾ ton diesel on County Road CC, Clint, 21, dialed Schumacher and heard his father’s remarkably calm voice on the far end of the horn: “I’m in the bin and can’t get out.”

Clint couldn’t process the literal nature of Schumacher’s words. “Dad? Did the door close on you? Why can’t you get out?”

“The corn,” Schumacher answered with no trace of alarm. “I’m in the corn and can’t move.”

The diesel truck jumped on the blacktop as Clint hammered the gas. He was in a race against corn and time.

(See related: Against All Odds: Farmer Survives Epic Ordeal)

Iowa: Entombed

For the moment, the respiratory mask was salvation. As the mask staved off suffocation and allowed oxygen to filter in through the kernels, Baker continued to sink straight down through the corn toward the churning auger and certain mangled death. Defying all reasonable odds, he felt his right boot make contact with metal—the auger gearbox. “I was about to be sucked in and shredded, except for my foot landing on top of the gearbox.”

Several minutes later, he felt the metallic hum cease as Rick shut off the auger and drove away to deliver grain. With Rick and Palmer both in transit, and a temporary respite from the auger, Baker was forced to wait, as motionless as a stone.

“After the auger shut down, I was still in panic for a few minutes, pushing and trying to wriggle free,” Baker describes. “All of sudden, I realized the more I struggled the tighter the grip of the grain. I could push against the grain and free my back a fraction of an inch. But that fraction was then lost to grain. I quit fighting and started thinking, ‘There is no way out. No way. Just be alive when rescue comes.’”

As Rick drove away at 10:32 a.m., he phoned Baker to make certain his son had exited the bin. No answer. Rolling down the highway, he began peppering Baker’s cellphone with calls and leaving messages. No answer. Concern mounting, Rick called Palmer and asked him to check on Baker and make certain the auger remained off. Returning to the farm after delivering a grain load, Palmer climbed the bin staircase, called for Baker and peered into the dim depths at a flat corn surface…and nothing else. He climbed down, called Rick, and reported: No sign of Baker.

Fearing the worst, Rick sent Palmer back up the staircase to check on Baker once more. This time, Palmer spotted the slack rope running down the ladder into the center of the corn like a fishing line reaching to the middle of a pond. Pulling on the rope, Palmer felt the tension go slack as the loop sloughed off Baker’s hand and rose up through the corn.

“I never heard a sound from Kay. I only felt the rope come off my hand when he pulled, and it left quite a burn, but I knew it might mean help was coming,” Baker explains. “They knew I was under the corn and about where I was.”

Empty rope in hand, Palmer shot down the staircase, phoned Rick, and delivered a body blow. Rick dialed 911, pulling the trigger on the fire department and local assistance. Despite all due speed, the reality was understood by all involved in the small agricultural community: The effort was likely a body recovery, and not a rescue. By fair estimate, Arick Baker was already dead, entombed in the corn.

Wisconsin: Concrete

Clint, alongside older brother Cody, scampered across the corn to Schumacher, still firmly planted to his armpits. “My own safety was not a concern,” Clint recalls. “I never even thought about another shelf breaking. Dad was in danger and all I thought of was to help; we weren’t even roped off.”

Dipping a bucket into the corn beside Schumacher’s chest, Clint repeated scooped away 5-gallon loads of kernels. No effect; like pails of water bailed from an ocean. After several minutes, two neighbors arrived and joined the scooping brigade. The effect of four men atop Schumacher for over 20 minutes began to take a predictable toll. The grain tightened, gaining in strength. “My legs were spread apart below me,” Schumacher recalls, “and I could feel myself slowly sinking, but my real worry was how bad the constriction was getting. Every step they took trying to save me made it worse.”

“I just thought if they could scoop down to my waist I could wriggle out. No way. Every scoop out seemed like it was replaced with two scoops in. Again, I can only compare this to being stuck in concrete. Concrete. I knew I was in trouble and finally said, ‘That’s it. Call for help.’”

Over an hour into the ordeal, the 911 bell was rung. However, the 60-plus minute interval came with a precipitous price. Schumacher’s breaths were getting shorter as the corn made its claim. The Wisconsin farmer was wearing down.

Iowa: A Stringed Puppet

Buried alive, Baker’s corn domain was an inky darkness devoid of light, surrounded by pure silence. Despite the lack of external stimuli, he could feel—but not hear—the maddening vibration of a cellphone in the pocket of his shorts. Fading in and out of consciousness, Baker struggled to cope as corn pressure crushed his lower extremities and progressively constricted his diaphragm with each exhalation. “Every breath was a gasp. It was like two grown men sitting on my chest. The pain was so intense, but in a way, the pain was good because it let me know I was alive. I couldn’t see or hear anything, but at least I could feel pain.”

Baker surrendered physically in order to mentally fight a ferocious battle for survival. His position in the corn was akin to a stringed puppet. Right leg straight down atop the gear box; left leg cocked forward in a running position; right arm straight out; and left arm straight up, with thumb and fingers poking just out of the corn canopy.

“It was almost more than I could bear. Three times I decided to end it all and held my breath hoping to fade away and die, but it didn’t work. My lungs kept drawing in tiny bits of oxygen and my heart kept beating. Later on, doctors estimated my heart rate under the corn was close to 245 beats per minute.”

At 12:37 p.m., two members of an emergency crew accessed the bin and began circling the grain above Baker, calling out and searching for clues. The added motion shifted the corn and buried Baker’s hand beneath 10” of kernels, hiding it from view. Unconscious, Baker was entirely unaware of movement above. “Somebody outside turned on the bin fan and the noise woke me up. I could hear a radio and voices, and started yelling for help. The guys dug like crazy and we locked hands. I knew I could come out of that bin alive.”

As word of Baker’s survival shot from the bin and rescue units realized the retrieval was a rescue, the intensity dialed to 11. Ten fire departments, two rescue squads, four ambulance crews, and a phalanx of community friends kicked into gear. Four holes were cut in the bin sides, with 15-plus people at each outlet shoveling grain away to maintain flow.

By 12:52 p.m., the rescue crew located Baker’s head—still safely tucked into the precious respiratory mask.

(See related: Against All Odds: Farmer Survives Epic Ordeal)

Wisconsin: Tough as a Cob

Block and tackle, emergency units dropped a rope from the top hatch of Schumacher’s bin and prepared to pull him from the corn. Harness in place and rope taut, Schumacher didn’t budge—period. “They couldn’t even wiggle me a fraction. The strain was unbelievable and they would have had to rip me in half to get me out. For sure, I wasn’t going up like that.”

Changing plans, the rescue team drove sheets of plywood into the corn around Schumacher, creating a box effect. Six hours later and several box collapses, Schumacher was plucked from the corn. “They shoveled down to my waist within the box and then popped me out, but the pain was unreal and the pressure tore my stomach muscles and caused a hernia. But the freedom felt so damn good. I can’t explain it, but I knew it wasn’t my time to die. I figured I was getting out, but I wasn’t sure how.”

“We were afraid the box just wouldn’t work and it went on for three hours or more,” Clint adds. “The timing of everything was crazy. The fire department was getting ready to cut holes in the bin when dad said, ‘I’m ready.’ They were able to pop him out of the corn literally at the moment they were cranking the saw below.”

“About 75% of our fire department is attached to farming and it was amazing to have those guys on the scene,” Clint continues. “There’s no way to thank them enough for the job they did.”

Tough as a cob, after a total of eight hours trapped in a corn vice, Schumacher climbed the inner bin ladder and walked down the outer staircase—by himself.

Iowa: Lazarus

By 1:17 p.m., approximately 25 minutes after finding the top of Baker’s head, the rescue team had corn cleared down to his neck, but the ordeal was far from finished. Baker’s extraction was a grueling ordeal and a saga unto itself. “Even after they uncovered my face, I was reburied five more times. The shift in the grain is tough to understand, but that’s how difficult it was for the guys to move the corn away from me.”

Using an aluminum cofferdam, and aided by the four-hole improvised drainage, the rescue crew freed Baker at 3:02 p.m., and pulled a Lazarus from the corn. The crew carried Baker out of the bin on a stretcher and placed him in an ambulance at the ready. Five hours of hell was over. Yet, loosed from the corn’s grip, Baker’s body recoiled from the physical backlash. “There was no more adrenaline. Mentally I was free, but physically my body wanted to shut down. Every piece of pain my brain had regulated or fought off came charging back. Pain was all I could feel.”

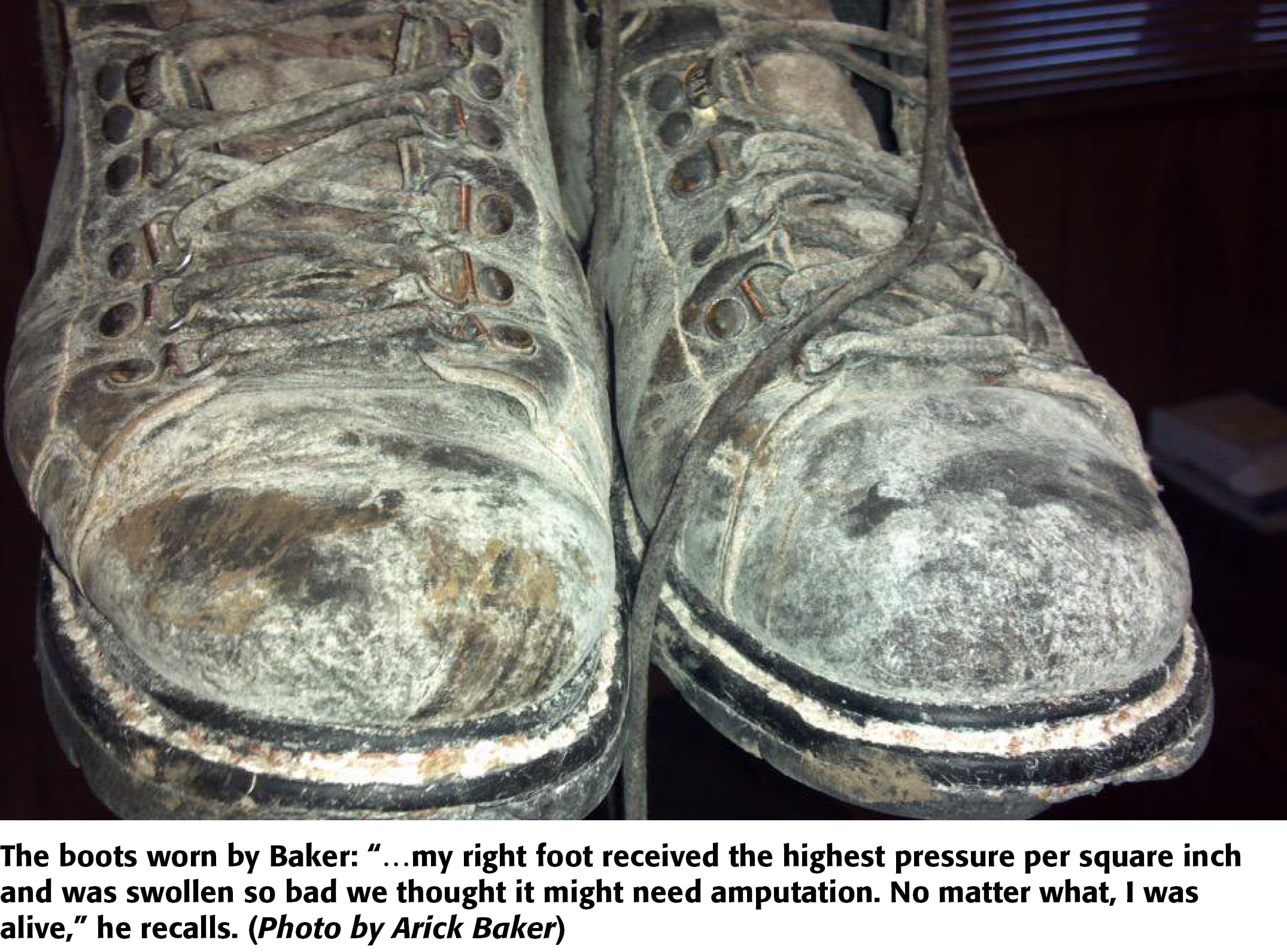

Thirty-two minutes after extraction, Baker arrived at the hospital with his heart rate still pounding—172 beats per minute. His body was covered in kernel marks and indentations. “I had open sores in places, and horrible acid burns where my right leg had soaked in the rotten shelf of corn. Being so far down into the corn, my right foot received the highest pressure per square inch and was swollen so bad we thought it might need amputation. No matter what, I was alive.”

Wisconsin: Lulled to Sleep

Nine years later, Schumacher’s mind revisits the entrapment every time he drives by the 49,000-bushel capacity bin. And inside the bin, his nerves tighten up. “Nobody goes in alone now. We bought several body harnesses and snatch blocks. I don’t care how many years you’ve been farming; you’ll make mistakes if you take shortcuts.”

“We don’t talk about the accident, but we live with the lesson,” Clint echoes. “Safety first. You do certain things your entire life on the farm and think there are no consequences. Shortcuts get us in trouble. Get wrapped in a PTO shaft because it was a shortcut instead of walking around a tractor. Get hit by a bull while getting a cow because it’s a shortcut. Pick up with a loader with no chain and get hurt cause it’s a shortcut. Faster is not better.”

“Farming is so pressure-packed,” Schumacher concludes. “I sped past a warning sign and paid for it, but the price could have been much higher. Farmers know what I’m talking about because that corn…that corn will lull you to sleep.”

A Single Mistake

Bill Field, the foremost authority on grain bin entrapments and engulfments in the U.S., and professor of agricultural health and safety at Purdue University, emphasizes the dangers of delay following the critical moments of an accident. “We haven’t seen many successes when a 911 call is delayed. Farmers are sometimes embarrassed or prideful and don’t want to call, but contacting 911 should be immediate. Every second is crucial and 5% to 8% of victims die with a head above grain when they eventually suffocate or give out after struggling. That’s how vital timing is, especially when you consider how far out of town most farms are and how long it takes for rescue crews or fire departments to arrive.”

In addition, Field stresses the hazards of rescue attempts atop the grain, citing stark statistics from manure pits as a parallel. “Twenty percent of all manure pit deaths involve someone helping someone else. The same principle applies to grain bin accidents. Also, people go in and pack down grain even tighter, or rescuers get exhausted in the grain. At all times, the number of people in the bin must be minimized.”

Over the past 40 years, Field has gathered the most comprehensive data available on grain accidents in the U.S., collecting the details on over 1,200 grain entrapment cases since 1970. “The vast majority of incidents happen with corn. Certainly there are some in soybeans and wheat, and even sunflower and canola, but overwhelmingly the crop is corn.”

“The science of grain movement means you can’t stay on top; you’re pulled into the flow, which is a relatively small column of movement with a funnel shape of about 25-30 degrees,” Field details. “The human body weighs about 2-3 bu., and if you’re running an auger drawing 2,500-5,000 bu. per hour, it only takes seconds to pull a person into the flow. There isn’t much forgiveness in grain movement and a farmer may only get to make a single mistake.”

Iowa: Bargain of a Lifetime

Tough as nails, Baker endured and survived one of the most harrowing episodes in agricultural history. He isn’t hindered by lingering physical effects or haunted by claustrophobia, but on occasion, inside a hotel elevator or confined spot, he tightens up and the bin memories return. Baker still goes into the 60,000 bu. bin, but never over the top.

“The corn fools us over and over,” he reflects. “Maybe our mentality to get things done overrules safety. Maybe it’s because we feel we’re not accountable on our own farms and we become blind to consequences. No more for me. My time is not worth more than my safety. Five minutes of stopping to think on Monday would have prevented everything I went through on Wednesday.”

Six years after Baker’s astonishing Lazarus-like emergence from the depths of a grain bin, the vital respiratory mask sits on a shelf in his basement. “Sixty seconds. If I hadn’t had the mask on, I’d have died in 60 seconds under the corn. It doesn’t really work anymore, but it sure served its purpose.”

Indeed. A $379 mask bought at a farm show on a whim? Bargain of a lifetime.

For more, see:

Against All Odds: Farmer Survives Epic Ordeal

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

Blood And Dirt: A Farmer's 30-Year Fight With The Feds

Future Shock: Farmers Exposed By US-China Long Game

Wild Pig Wars: Controversy Over Hunting, Trapping in Missouri

Agriculture's Darkest Fraud Hidden Under Dirt and Lies

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer