Judas Goats: Agriculture’s Bizarre, Drug-Addicted Masters of Deceit Once Ruled the Killing Floor

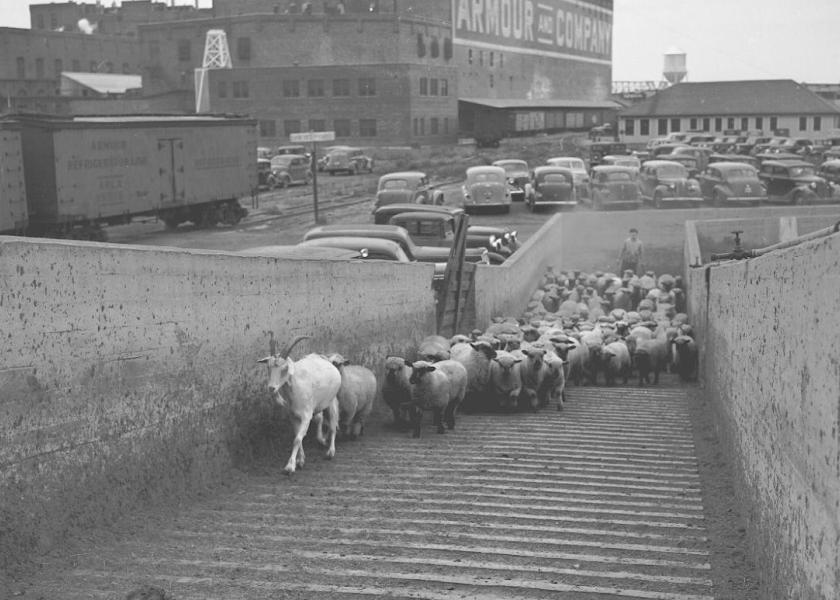

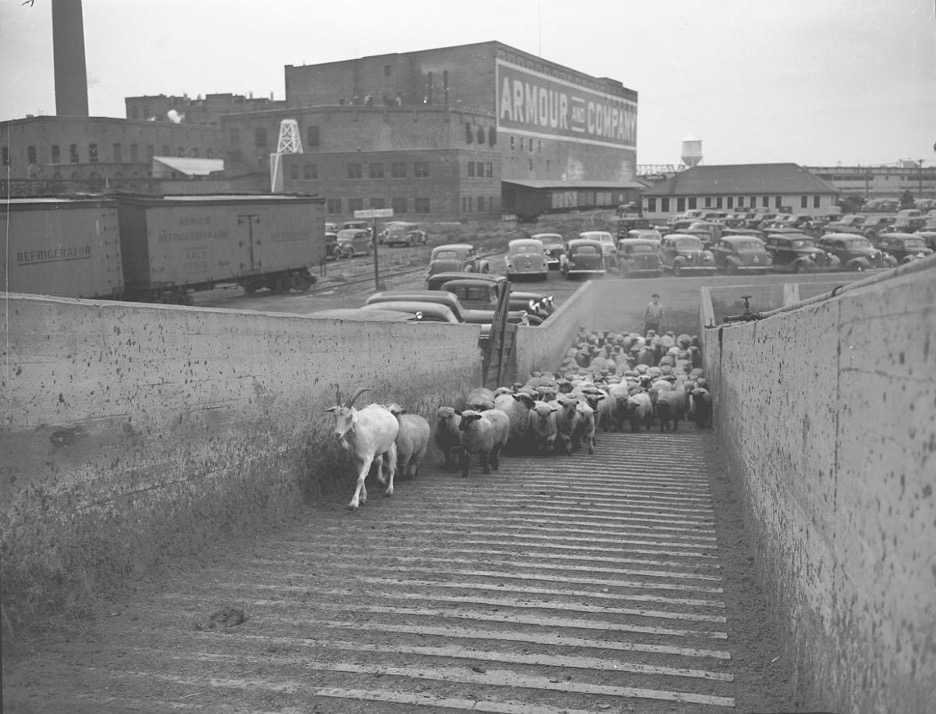

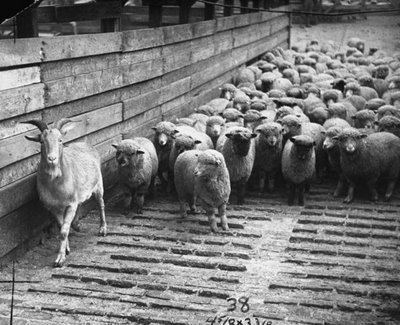

In one of the most bizarre spectacles in agriculture history, nicotine-addicted Judas goats once led sheep to slaughter down livestock’s version of the green mile. The aptly named Judas goats, rewarded with a single cigarette for every herd of sheep deceitfully escorted to the killing floor, were once key players in meatpacking plants.

It strains credulity to envision the surreal parade of a lone goat leading sheep across a meatpacking facility, coaxing the flock up concrete ramps, delivering the herd beyond the point of no return, and then hustling toward a nicotine fix and a repeat performance. However, Judas goats were part-and-parcel of livestock slaughter, and their history sheds a fascinating light on a bygone era. Betrayal by bleat and tobacco.

And a Goat Shall Lead Them

Gravity is free.

The slaughterhouses of yesteryear were multi-level structures, sometimes five or six stories in height, with each floor housing a specific function related to animal processing. The killing floor occupied the top level and served as a conduit to further processing on the floors below via a network of chutes, pipes, and drains that accommodated blood, offal, hide, bone, and meat. A living cow, pig, or sheep entered the killing floor on top of the slaughterhouse and met with a sledgehammer or captive-bolt, and descended each floor in bits of appreciating value, i.e., eventually exiting the bottom floor as packaged bacon or a side of ribs.

However, theory is tighter than practice. Getting large quantities of livestock to the top floor, a space bathed in the smell of death, required systematic efficiency. Cows could be cajoled; pigs could be coaxed; but sheep were a breed apart—an entirely different proposition.

Enter the Judas goat.

Pandemonium Awaits

In extreme western Iowa, rubbing against Nebraska and South Dakota, Sioux City sits at the navigational head of the Missouri River. The town is synonymous with U.S. meat packing history. Packing giants Cudahy, Armour, and Swift (all shuttered by the late 1960s) were massive presences in Sioux City, and at each facility, Judas goats held sway.

“It was pretty simple,” says Greg Dunn. “You couldn’t get sheep to the top floor without a goat. Every plant had Judas goats.”

Dunn, 80, spent a lifetime in the meatpacking arena as a vice-president for IBP and Tyson. As a 10-year-old in Sioux City, Dunn began trailing the shadow of his father, Bill, a buyer for a local grocery chain, through local meatpacking plants, and Dunn worked at Swift during high school and college summers.

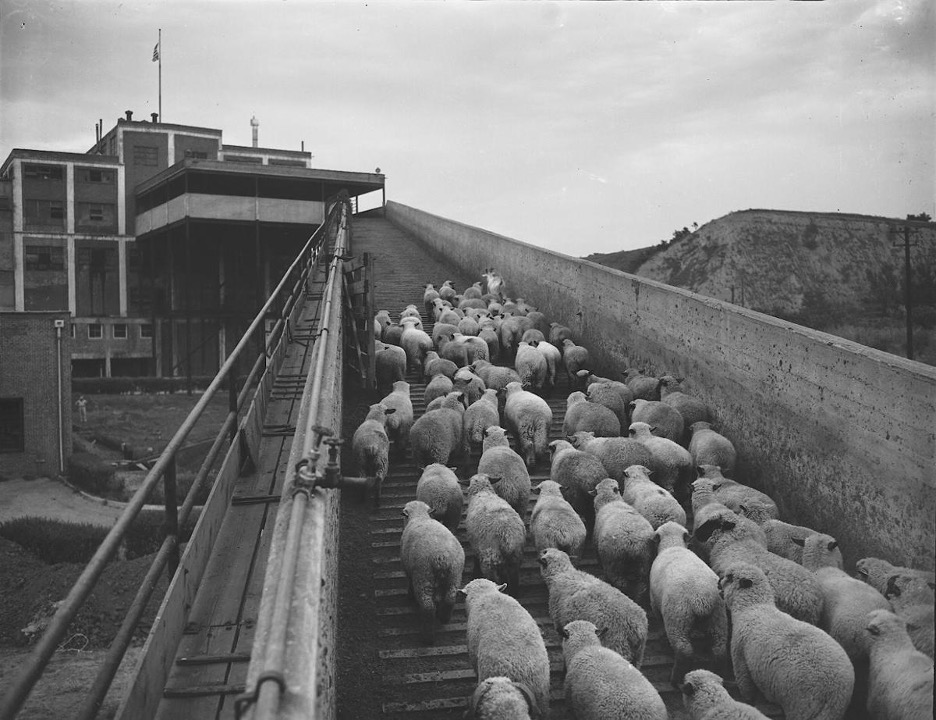

Swift’s gravity-reliant, six-story plant ran five days per week. Yet, across decades, how were millions of live animals taken to the uppermost level? The plant was buttressed by massive, walled ramps that zigged and zagged up the sides of the building. On a steep incline, with grooves cut in the cement to provide footing against the steady accumulation of feces and waste, livestock ascended the ramps and funneled onto the killing floor.

“The cattle and pigs were relatively simple to send up the ramp,” Dunn says. “Even if they got startled and balked, you could convince them from behind to keep moving and go up.”

“Not so with sheep,” he continues. “Their own instinct would push them in a constant circle. They wouldn’t follow a person, and you couldn’t even use a dog because the sheep would get scared, bump into the chutes, and maybe break their legs in such tight spaces. I’m talking complete pandemonium. The only way to calmly get them on the killing floor was a goat.”

Dunn estimates the ramp journey was roughly an eighth of a mile. “This was normal in the livestock industry back in those days and I know it had been in use way before my time. One goat could lead 30, 40, or even 100 sheep. The trick was to get them started and that’s why you needed a Judas goat in on it.”

Hooked on Leaf

At Swift, during Dunn’s tenure, the Judas goat of choice was rightly dubbed “Billy,” and occupied a designated pen of his own, where he lounged—collared and belled—until needed. “Every plant had at least one Judas,” Dunn says, “and these were very valuable animals.”

On arrival of sheep to Swift, Billy knew the routine, recalls Dunn.

“We’d take the goat and put him in front of the sheep. Up the ramp they’d go, following Judas. If the sheep hesitated, Billy would bleat to keep them moving. If they didn’t come, he’d stop, turn around, bleat more, and wait for them to catch up.”

Story by story, the procession moved skyward, following the lead of the Judas goat to the killing floor. The ramps were devoid of human presence to ensure the sheep didn’t break. At the pinnacle, on the sixth floor, a single doorway led to the final point of debarkation.

“At the top, it was just the Judas goat and the sheep. There was what I’d describe best as a closet with no door, and the Judas goat would step aside in there and every single sheep would file right in. After the last sheep went by, he came back down the ramp to get his cigarette.”

The goat was trained on unfiltered cigarettes, particularly one Camel or Lucky Strike per trip, specifies Dunn. “He ate it whole. He loved it because he was addicted to nicotine. Everyone knew to be careful when you leaned over to give him the cigarette because he’d reach into your shirt pocket, steal the whole pack, and run away to eat it.”

Nicotine also was the carrot used to season every understudy. In training a successor goat, meatpacking plants tied a younger candidate behind a Judas goat with a 3’ rope. The pair made the ramp trips together for several months, each receiving the standard single cigarette reward. In short time, the junior goat learned the routine—and was hooked on leaf.

“What a testament to man’s ingenuity and nicotine’s power,” Dunn says. “You have to wonder how long Judas goats have been in service. There’s no doubt it was way, way before my time.”

Escapees

On Nov. 30, 1912, Pacific Rural Press published an article describing the Judas goat system, and cited details provided by Denver Farmer (which closely match Dunn’s account at Swift in Sioux City):

At all the large stockyards of the country the packing firms have bell goats for leading sheep from the sales pens to the chutes at their slaughtering houses … when sheep are purchased they are led instead of being driven, and the leader of the sheep is not a man, but a trained goat. Each firm has a trained goat of its own, and frequently several of them. From the sheep sales pens to the chutes the way is devious, often through many gates, across streets and tracks, under sheds and elevated structures and full of so many crooks and turns that only a wise man or a trained goat could ever find the way. So when a bunch of sheep has been purchased the bell goat is placed at their head and he leads the procession. An attendant follows to open and close gates. The sheep follow the goat in one solid mass without deviation. When the slaughtering pen is reached a gate is opened and the goat goes in with all the sheep following. At one side a small gate is opened for the goat to go out, but the sheep which have been led to the shambles and their last pen are closed in. The bell goat takes his own course over the city streets, or wherever he will, on his way back to the stockyard’s sheep house.

“To really understand Judas goats, you have to realize that goats are highly intelligent creatures,” Dunn says. “We had to double-latch gates because the Judas goat at Swift figured out how to open them, and he’d still escape frequently. He was so valuable that the plant would be frantic, desperate not to lose him. Most of the time, he made his way to the parking lot where he’d get on top of a cars and look around. We’d have to climb up and grab him to get him down.”

“Each goat worked for a long time, at least several years, and the whole plant knew exactly how important the goat was,” Dunn continues. “In the 1950s, there was a big flood here on the Floyd River that swamped the adjacent stockyards. A Judas goat got caught in the flow and two guys jumped in and risked their lives to save it. That tells you the high, high value of a Judas goat to a meatpacking plant.”

Sinners and Saints

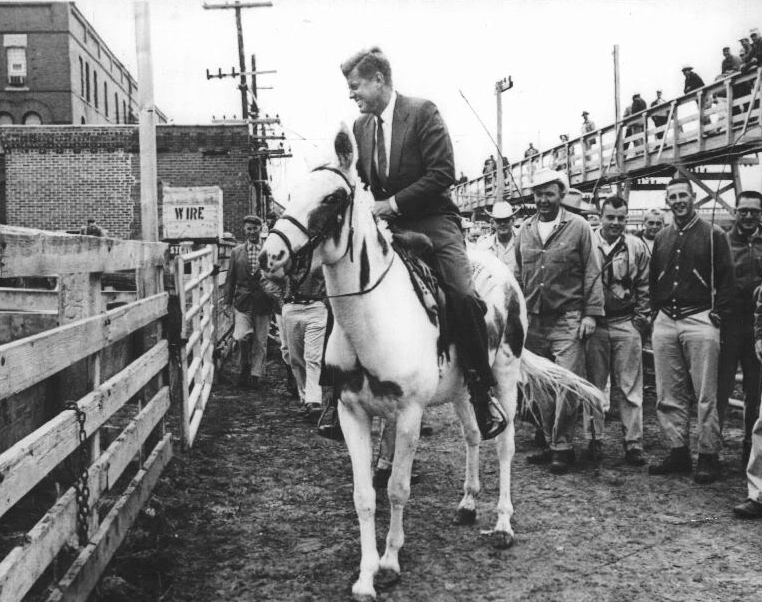

George Lindblade, 85, is an icon of Sioux City and a living legend in the photography industry. Starting with a box camera at age 7, Lindblade’s career carried him across the U.S. in pursuit of the majestic and mundane, and compelled popes, presidents, politicians, musicians, and pop notaries to cross his lens. Whether shooting documentaries or commercial photos, Lindblade has eyeballed the rare air of forgotten history—including Judas goats.

The realm of the Judas goats—the stockyards—was a universe unto itself and a well that never ran dry for Lindblade’s photographic and story needs.

“The stockyards pumped out backyard invention and ingenuity almost on a daily basis,” he explains. “Most people don’t know what the hell a cripple cart was, but animals—whether coming in on a train or truck—might suffer an injury or get a broken leg. There was a contraption—a cripple cart—with some straps to pick up these 1,000-plus-pound animals and take them to slaughter. If it was a bad injury, the big three would pass, and you’d take the animal to a small packer for custom cutting.”

The color of personality within the stockyards was tailor-made for a Hollywood script, Lindblade explains. The characters often were a law unto themselves. “Most of the guys were commission men who bought and sold livestock and had lots of time on their hands for bullshitting. Most of the talk would land you in jail today, but back then, it was fun and humorous.”

Cattle, bars, strip joints, fights, gambling, and one-upmanship created a surreal scenario with oddities such as Judas goats and cripple carts hovering in the periphery. “It was old-school and you never knew what you might hear or see,” Lindblade says. “These were guys that made a lot of money, spent a lot of money, and they played with a lot of money.”

Sinners and saints, Lindblade describes. “If you crossed the men of the stockyards, they’d get you politically, socially, and financially. Sudden death. Leave them alone. Nobody screwed with the stockyards. Yet, any charity that came through the doors was helped by the same hard men who didn’t give a damn who you were: Their attitude was to instantly help and not ask for a receipt.”

Since God Invented Dirt

In the background of human drama and posturing played out each day in the stockyards, the Judas goats maintained their reign.

“The goats were Yankee ingenuity at its best,” Lindblade adds. “Without modern technology or automation, people used nicotine and a goat to move large numbers of animals from point A to B up steep, steep ramps.”

“It was once a normal part of agriculture, but you just couldn’t make up the world of the Judas goats and stockyards now because it seems too crazy, but it’s a missed society as far as I’m concerned.”

In capsule form, Lindblade fittingly punctuates the duplicitous role of meatpacking’s bearded pipers. “Let me tell you how effective these animals were,” he concludes. “I’ll bet Judas goats have been around since God invented dirt.”

To read more stories from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com 662-592-1106) see:

Cottonmouth Farmer: The Insane Tale of a Buck-Wild Scheme to Corner the Snake Venom Market

Tractorcade: How an Epic Convoy and Legendary Farmer Army Shook Washington, D.C.

Bagging the Tomato King: The Insane Hunt for Agriculture’s Wildest Con Man

While America Slept, China Stole the Farm

Bizarre Mystery of Mummified Coon Dog Solved After 40 Years

The Arrowhead whisperer: Stunning Indian Artifact Collection Found on Farmland

Where's the Beef: Con Artist Turns Texas Cattle Industry Into $100M Playground

Fleecing the Farm: How a Fake Crop Fueled a Bizarre $25 Million Ag Scam

Skeleton In the Walls: Mysterious Arkansas Farmhouse Hides Civil War History

US Farming Loses the King of Combines

Ghost in the House: A Forgotten American Farming Tragedy

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Evil Grain: The Wild Tale of History’s Biggest Crop Insurance Scam