The Arrowhead Whisperer: Stunning Indian Artifact Collection Found on Farmland

Hidden for thousands of years beneath farmland, arrowheads wait patiently for the eyes—and hands—of Johnny Dickerson. Blue jean pockets empty after an hour spent tracking dirt rows beneath an unusually brutal spring sun, Dickerson methodically scans the ground for a hint of flint, and even the tiniest speck or flake drives him to keep the faith and continue searching. As fatigue begins to creep onto his shoulders after five miles of walking, Dickerson’s mouth suddenly goes dry and his stomach tightens—he can feel an arrowhead in close proximity, sight unseen.

Minutes later, sparked by an unmistakable sensation in his core, Dickerson’s gaze drops to an outrageous flint point, rain-washed with ears, tip and base in pristine condition, as if the worked rock was gently dropped yesterday. He puts a knee in the soft, sandy soil, reverently picks up the arrowhead, and feels his adrenaline surge as he tucks it into a denim pocket. Three more hours of hunting? Four more hours? Not a problem.

The flint artifact and a dozen more points subsequently found on the same hunt are destined for Dickerson’s phenomenal collection of Native American stone tools, including 4,000-plus showpiece points. Dickerson, an arrowhead hunting warhorse with a bootstrap tale and little regard for conformity, is a classic American individualist. There are many arrowhead hunters—but there is only one Johnny Dickerson.

Cochise and Cash

On a May afternoon on the outskirts of Moultrie, 200 miles below Atlanta in southwest Georgia, Dickerson, 71, is returning home from another successful hunt at one of his countless arrowhead sweet holes, and barreling down blacktop in a white, single-cab F-150 propelled by an abnormally loud motor, with the bare bones bass-baritone of Johnny Cash blaring through the cab. Leaning back from the wheel, Dickerson’s black hair and dark features are prominent, testimony to the Native American blood in his veins—he is a quarter Creek and looks the part.

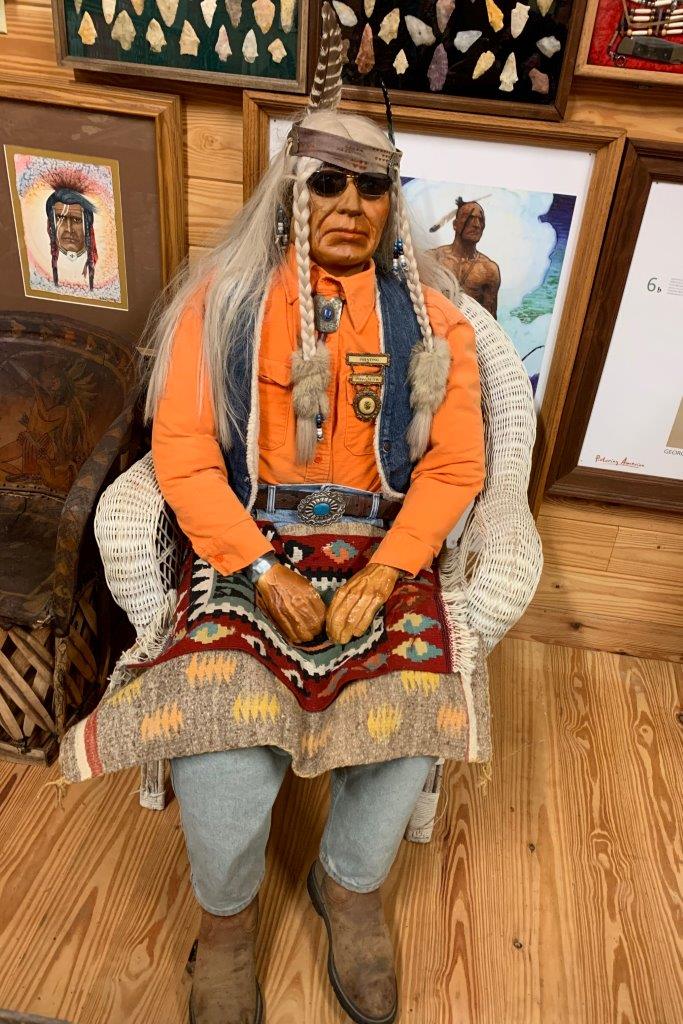

Dickerson typically hunts solo, but on this drive back to Moultrie, he is not alone: Silver-haired Cochise is riding shotgun. Lips pursed and jaw square, wearing dark sunglasses, an orange, long-sleeved collared shirt with accompanying bolo tie, turquoise belt buckle, denim vest, faded jeans, leather work boots, two front hair braids, and a headband flanked by a lone, upright turkey feather, Cochise stares sternly ahead as a succession of cotton and peanut fields blend in the rearview mirror. A frequent passenger in Dickerson’s F-150, Cochise is half mannequin and half cigar store Indian, with wooden arms and legs, a stuffed torso, and a life-like, plaster head topped with light gray horsehair.

At a four-way stop outside Moultrie, Dickerson, 71, slows to a halt as Cochise catches the eye of several bewildered pedestrians in the lot of an adjacent convenience store. For a few seconds the vehicle pauses, followed by the spin of tires and the squeal of rubber on asphalt, as the truck hot rods out of the intersection and lurches down the Colquitt County road carrying a most motley trio: Cash, Cochise and Dickerson.

X Marks the Spot

Every morning, rain or shine, Dickerson’s feet hit the floor at 3:30 a.m. Retired after running the show at Spence Field (a former air base and current industrial park) for 22 years, and now filling hours as a part-timer, he works from 7 a.m. to noon, four days a week. Work is piggybacked by an afternoon constitutional, a 1-hour and 15-minute nap commencing at 1 p.m., on the nose. Bedtime follows at 9:30 p.m., end of story. The regimen, despite its unorthodoxy, suits Dickerson to a T: “I still work and I still get my sleep, no alarm clocks required. Yeah, I’m a little different, but nobody can hunt arrowheads seven days a week, all day. Not even me.”

How to explain the motivations of a true maverick and the origins of a massive Native American artifact collection? Boy to man, it’s best to go back to the beginning.

Dickerson was born on the bottom of the social ladder in 1949, and grew up in sharecropping poverty on a five-acre plot outside the tiny town of Funston in Colquitt County. Even into the late 1950s, Dickerson worked on occasion with mule teams, among the last echoes of livestock-drawn agriculture in the U.S. His father ruled the household with an iron hand, and kept hogs for a nearby farmer, and the tiny Dickerson and his brothers were charged with the constant care of 500 head—an incessant cycle of mixing potash lye, water and corn to ensure soft grain for the pigs. “As a little boy, it wasn’t easy to live in that house, and I had to work my tail off to survive; that was life,” recalls Dickerson, in an easy south Georgia drawl. “I still remember that every time a hog was born, we’d get needle-nose pliers and break off the sharp teeth to make sure they wouldn’t tear off the momma’s teats. Those memories are clear as can be.”

Trips to the service station were often hog-related. “I’d go collect burnt motor oil and take it home for the hogs. As soon as we castrated the males, I’d sop the burnt oil on the spot and they’d be fine.”

Dickerson was also responsible for another hog-tending job, a perplexing X-marks-the-spot task he never fully understood in the moment. Wielding a cigar-sized grease pencil, Dickerson would enter a pen of 50 sows and conduct a bit of breeding science. “I had to walk up behind and grab the sows at the top of the butt. If they stood there and didn’t move, you drew a big X on their back. If they ran, you left them alone. That was standing heat, a test to see who was ready. Then we’d cut the herd and go to the woods and get the boar, and they’d all get to breeding.”

One Little Rock

Beyond the hogs, and depending on the month, life was a chain of stacking hay bales, cropping tobacco, chopping weeds—and picking cotton, the gateway to an obsession with Native American artifacts. Even by 1960, only 60% of cotton was mechanically harvested, and cotton states were still serviced by an army of human pickers. In addition, although large-scale chemical defoliation to remove foliage prior to harvest began in Stoneville, Miss., in 1942, the defoliation practice wasn’t common in Colquitt County during Dickerson’s youth. Translation: When Dickerson dragged a 76”-long canvas sack through the fields and picked cotton as a child, the dirt rows weren’t obscured by dessicated plant matter.

On a late-August afternoon under a blinding sun in 1958, barefoot in a cotton field, and reaching to pluck white fiber from a boll, nine-year-old Dickerson spotted a triangular stone under a thin layer of light-brown dust—an arrowhead. “I picked it up and turned it over and over in my hand, amazed by what I’d found. Even as a little kid, I knew that nobody had touched it for thousands of years. It had no money value and nobody in the whole world cared about it, but I dropped it in my pocket; it was mine. In a time of slim pickings, it was something to call my own.”

Later that evening, Dickerson pulled the magical point from his pocket and gave it an honored spot in the security of a bedroom drawer, alongside a broken pocketknife and a handful of marbles. “That’s how it all began,” he remembers. “Hard to believe, that one little rock grew into more arrowheads than I could truly ever count.”

Standing atop the Acropolis

As Dickerson’s drawer filled with arrowheads, he seized on every month of crop season to help his mother scratch enough coin for school clothes and basic staples. “At grammar school, I knew I wasn’t dressed decent like the other kids, and it bothered me bad. Especially in summer, I’d hit every farmer that would have me and work tobacco, hay or cotton, saving every cent. Then before the school year started, I’d take my money to J.C. Penney and buy shirts, jeans and a pair of combat boots. That was my get-up and I was so proud to help my momma.”

However, Dickerson’s hardscrabble childhood turned to genuine turmoil in his teens, and his life took a Dickensian twist in roughly 1962, when his domineering father turned him out of the house and onto the street. As a ninth-grader, Dickerson lived in a room above the Moultrie YMCA, working after school for his board, keeping an eye on a means to make himself. When he finally walked the graduation line, Dickerson knew the Vietnam War was about to come calling, and he beat the draft board to the punch, literally flipping a coin to choose a branch of service.

“It was heads to join the toughest boys in the world and the Marines, or tails to see the world with the Navy. Tails won.”

After boot camp in Orlando, Dickerson returned to Moultrie for a brief visit, and received his marching orders stationing him in Charleston, S.C., along with instructions to fly out of Atlanta on Dec. 23, 1969. “I was grateful to be stationed so close to home, and I jumped on a commercial Delta flight and flew on a plane for the first time in my life.”

Three hours into his inaugural flight out of Atlanta, Dickerson signaled to a stewardess. “I said, ‘Ma’am, I’ve never flown, but I didn’t have no idea Charleston was so far.’ She answered back, ‘Charleston? We’re going to Athens.”

And much to Dickerson’s surprise, the stewardess didn’t mean Athens, Ga. “I don’t even know how many hours later it was, but we finally landed in the country of Greece, and I was sorta in shock.”

The country boy who cut hogs, picked cotton and cropped tobacco, spent Christmas Eve in Athens, standing atop the Acropolis, 5,800 miles from Moultrie. Four years later, and his military service complete, he returned home to a job with Cloudburst Irrigation, and his arrowhead passion, forged during childhood, exploded.

Leaving Time Behind

Roughly 50 years later, with a wealth of geological and historical knowledge to back his passion, Dickerson has amassed a stunning collection of Native American stone tools: thousands of points, blades, celts, boatstones, hammer stones, drills, hoes, bone implements, banner stones, gorgets, blades, chunky stones, and innumerable broken points and percussion flakes. “It’s not about counting them, because others guys have even more. It’s not about how much they’re worth, because I don’t care and I’m never selling. It’s not about finding them, because I truly take joy in the whole process of looking. I can’t even put words to how much I love it.”

“There’s times when I’m alone in a field and I’ll get an extra-sensory feeling when I know I’m getting close to an arrowhead, and it is very real,” he continues. “I can’t back it up with science, but this is a real feeling. Sure, some people just think my mind is getting head of my eye, but some guys out there know exactly what I’m talking about. It’s like a magnet begins pulling you toward an arrowhead location, and within a few minutes, sure enough, it’ll be right there in the dirt. You can’t pay money to match that feeling.”

Dickerson usually hunts alone, and the solitude is sometimes overpowering, he contends: “You can get lost in the middle of a field even though you know your exact location, because you leave time behind. There’s echoes from the past in those fields, and you hear them if you listen close. I mean sometimes you can stand in a spot and feel the stories. I think it all boils down to the essentials during a hunt: It’s just you, God, and the arrowheads.”

Pretend Indians

Typically, Native American sites are found near water sources, but deciphering the combined effects of farming, land forming, movement of water channels, clear-cutting and natural erosion is far from an exact science. “It’s a lot more than knowing where the water is—it’s knowing where the water was,” Dickerson explains. “Most of the time creeks, natural sinks, and bottoms all have arrowheads close, and you have to go look on the high side. My prime time is spring, after tillage, and after heavy rains.”

“If we get a hard rain, maybe a couple of inches, my stomach tightens up and I get excited, because I know at the right hunting spot the arrowheads will be sitting up like golf tees. And you never know what else you’ll stumble across. I found a broken pottery piece where a squaw was making something out of mud and left four finger impressions where she squeezed. It’s those small, unexpected details that make things amazing and come to life.”

Dickerson’s technique is methodically simple: He carries a picker-upper and stays in a single row, casting his eyes out no further than 4-6’. A clearly spotted arrowhead results in a hand extraction, but everything else is examined with the rubber ends of the picker-upper.

Occasionally on hunts, Dickerson draws a blank, but his keen eye typically locates multiple points. A decade back, he found 17 museum-quality specimens in a single day, and several years ago, had an even more bountiful hunt around a natural sink between two plowed fields, following a 4”-rain. “There was an acre pond in the middle with a natural spring and creek down below—a double water source for Indians. I found 40 arrowheads, tomahawk heads, nutting stones, mortars and so much else. One of the most glorious hunts I’ve ever had.”

Whether he finds a little or a lot, his thoughts are always consistent: “I’m kneeling in the dirt holding a rock that’s been hidden for thousands of years, and it’s truly a magical, special feeling. Whether it’s a 5,000-year-old adena, or a 10,000-year-old paleo, I start asking the same questions. Who made this? Who was he? Was he a leader or just a guy trying to survive?”

What role does a Native American background play in Dickerson’s love of arrowheads? Not much, he insists. “I do it because I love it and it doesn’t relate to me being a quarter Creek. Hell, everybody wants to be a Cherokee, anyhow. There are a lot of pretend Indians out there, and I’m not like that. I’ve got a turquoise ring and I love Indian culture, but I’m just who I am.”

Fakes and Thieves

The majority of Dickerson’s finds receive a permanent spot in an unlikely storage building on the back of his property. Step through the door of the metal structure and enter a 15’x25’ room lined floor, ceiling and walls, with unfinished #2 tongue-and-groove knotted pine. The museum is jam-packed with 50 years of finds and Native American-themed paraphernalia. Stone tools by the thousands rest on tables or wall boxes, along with pictures and photos, ceramics, lamps, rugs, jewelry, figurines, as well as several 4’-6’ life-sized Indians made from mahogany. On the far side of the room, seated in a white wicker chair, is the unflappable Cochise, silently watching over it all.

“I guess I’ve found about 4,000 really nice arrowheads in my life, and those are just the really good ones. It might be more, but I’m not about to count them for an exact number. It’s never been about having the most arrowheads. I know people with collections twice as big and bigger. Anytime you think you’re the man with a big collection, go to an Indian artifact show and you’ll say, ‘Dang, I’ve got nothing.’”

“I usually dump all the tater-chip sized flakes from my hunts outside the museum, and I may find enough to fill up half a 55-gallon drum after five or six hunts. One time, I dumped about 500 broken arrowheads outside, and my friends starting picking them up and taking them. No, no,” he laughs. “I value those too, but they were just there for kind of decoration.”

His fascination with ancient stone tools has given Dickerson a keen awareness of the dark side of the hobby—reproductions and theft. “There are guys out there who make and sell fakes, and there are also some flat-out thieves.”

In the summer of 2014, Dickerson’s phone rang with a call from Roy Godley, a Moultrie resident with a noted arrowhead collection. Godley’s house had been burglarized and the thief had taken his arrowheads, valued at over $10,000. “Roy called and asked if I’d bought any arrowheads or knew of any for sale. Roy is a good fella and I felt awful for him, and told him I’d dang sure call if anything crossed my path.”

Months later, in October, Dickerson got another phone call, this time from an individual with arrowheads for sale, purportedly all finds within 20 miles of Moultrie. “This guy was a criminal, or con-man, or whatever you want to call him, but he was friendly and smooth and looked kind of outdoorsy. He showed up the next day at my house with a sack full of really nice arrowheads, all bouncing around off each other in the bag. That should have been my first alarm that something wasn’t right.”

“My second alarm was that some of the points weren’t from around this area. I know what I’m talking about on the flint and these were not all native points.”

Dickerson handed the man $200, with promise of an additional $100. The following day, Dickerson delivered the final $100 at a service station link-up. With the deal completed, Dickerson dialed Godley, drove home, and spread the points on a table. “Roy walked in, saw the arrowheads almost from the doorway, and hollered, ‘Those are my damn arrowheads. You gotta be s******* me.’”

“Roy had pictures on his phone to back up what he said, and we called the law and the guy did jail time, and Roy was fortunate—really fortunate—to get his collection back. Most of the time, the stories don’t end like that.”

One-of-a-Kind

As Dickerson enters the final quarter of his life, what will happen to the stone tools he’s accumulated? The entire collection will eventually pass to his wife, Joyce, daughter, Jenna Alderman, and son, Asa.

Parts director at Lasseter Tractor, Asa lives alongside the Ochlockonee River. In 2015, directly behind his home, Asa bought 35 acres that rubbed against the Ochlockonee, and while clear-cutting the pines, found a heavy scattering of flint chips. He replanted the ground in pines, but a year later, at Dickerson’s urging, Asa removed the trees from five acres of sandy ridges that bumped the water, opening a door on prime arrowhead territory. Periodically, Asa harrows with a 5045E John Deere tractor, exposing stone tools hidden for centuries—and sometimes millennia.

Asa’s ground has given up several hundred arrowheads, with the elder Dickerson finding the vast majority. However, Asa recalls a day when the script was flipped at another location, and an 8-year-old boy found his first point. “My daddy can find them like nobody else, but I’ll never forget my very first find, back when I was 8. We were in a field, and I was about 6’ behind and 6’ to his left. I wasn’t even hunting hard and I saw him walk right past one—a really good one that was the same color as the red clay dirt. I haven’t brought it up in a whole lot of years,” Asa laughs. “He might not remember it, but then again, I don’t even know if my daddy will admit to it.”

Dickerson’s daughter, Jenna Alderman, and her husband, Benji, own Sundown Farms Plantation—a picturesque quail hunting, wedding, and corporate event site, roughly a mile from Dickerson’s house. “It’s ironic because when I was a kid, we never hunted wildlife—we hunted arrowheads,” she recalls. “So many Saturdays, we’d stop at a gas station on the way to hunt, stock up on candy and drinks, and then spend all day in the arrowhead fields, maybe playing in a creek while daddy hunted. They were wonderful, fun times.”

Why does Alderman believe arrowheads have such a hold on her father? “He grew up so poor and rough, and it’s possible his past made him view them as precious and something to call his own. He came from nothing, worked so hard, and I wouldn’t trade him for nothing, and I find myself turning into him.”

“He’s truly one-of-a-kind. Sometimes my friends will text me and say they just passed my daddy and Cochise driving down the road. I mean, there is honestly nobody like him.”

To the Last Arrowhead

Despite a lifetime of hunting, and a deep attachment to Native American lore, arrowheads don’t rank No. 1 in Dickerson’s life, or come close, he explains. “My family, and not arrowheads, drives me. I do love arrowheads deeply, but nothing compared to my wife, kids and grandkids. I’m a man that’s a little crazy, with a little bit of a crazy past, but if I died today, what a wonderful life it’s been in this great country. I just look at the opportunity my family has and how well they’re doing today, and I realize my grandkids will never have to save money in the summer just to buy school clothes. That’s a tiny part of how grateful I am.”

“I have my family around me and I’m free to hunt arrowheads. What else could I ask for? As long as the Lord keeps me able on this Earth, I’ll be hunting arrowheads. As far as I’m concerned, I’ll never find my last one.”

For more, see:

Fleecing the Farm: How a Fake Crop Fueled a Bizarre $25 Million Ag Scam

US Farming Loses the King of Combines

Ghost in the House: A Forgotten American Farming Tragedy

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Misfit Tractors a Money Saver for Arkansas Farmer

Predator Tractor Unleashed on Farmland by Ag's True Maverick

Government Cameras Hidden on Private Property? Welcome to Open Fields

Farmland Detective Finds Youngest Civil War Soldier’s Grave?

Descent Into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

Evil Grain: The Wild Tale of History’s Biggest Crop Insurance Scam

Grizzly Hell: USDA Worker Survives Epic Bear Attack

A Skeptical Farmer's Monster Message on Profitability

Farmer Refuses to Roll, Rips Lid Off IRS Behavior

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Shattered Taboo: Death of a Farm and Resurrection of a Farmer

Frozen Dinosaur: Farmer Finds Huge Alligator Snapping Turtle Under Ice

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer

Corn Maverick: Cracking the Mystery of 60-Inch Rows