Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming’s Greatest Show on Legs

Welcome to four hours of rat hell and a hunt like no other. Bones break and blood spills across a farm yard, in unison with a frenzied cacophony of guttural snarls, as a terrier pack flushes a nest of rats and an absolute melee explodes. Nature unleashed. Punctuated by manic barks and desperate whimpers—dogs descend like raptors, snatching and ferociously shaking rodents in a blur of motion that cuts the air with staccato slaps and snaps vertebrae. The fury traps time in the freeze-frame of a primal moment, only broken when the last rat is dispatched and the lust subsides.

Jordan Reed is the conductor of a canine orchestra tackling one of agriculture’s most pervasive financial drains—rats. All told, rats rack up $20 billion in damages to the U.S. economy each year, and agriculture presumably foots a massive chunk of the bill. Reed provides an extermination service for farms and feed lots with a highly efficient team of rat dogs unique in the agriculture industry. When Reed unleashes the pack—the Mongrol Hoard—on a farm lot, he leads from the middle of the scrum, ensuring the organized chaos stays a shade away from complete mayhem. Trimmed down, Reed’s Mongrol Hoard may be farming’s greatest show on legs.

The Dogs of War

On a small farm in southern Oregon’s Josephine County, the team of terriers darts around Reed’s property as he walks toward a shed. Noses to the ground sucking in scent, ears pointed in permanent radar position, yet eyes trained on Reed, the canine squad fixates on his every move and waits with straining patience for a telltale sign of deliverance, as seconds expand to minutes and then seemingly stretch to eons. Finally, Reed delivers the pack from torment—by grabbing a shovel—and the terriers begin to bounce and twitch, muscles trembling, in anticipation of what is about to go down. No windup, no warmup required. At the mere touch of a shovel, the dogs of war are triggered and ready to rumble.

“Helluva hunt,” Reed says. “From start to finish, rat hunting is as primitive as it gets. Raw.”

Sporting colorful names—Piper, Peanut, Squeakers, Nessie and Scruffy—the dogs are predominantly feists, a breed claimed by many hunters as the epitome of a hearty hunting companion. Once a feist owner; always a feist owner. Typically 15-30 lb. in weight, the relatively small, long-legged breed possesses a phenomenal engine conducive to constant pursuit and activity, i.e., small game lasts like a snowflake in summer.

As a boy, Reed owned several half-breed feists, and recognized their special nature, but the idea to channel the dog’s energy into agriculture was largely serendipitous, particularly since Reed’s family wasn’t involved in hunting or farming. Four walls never suited Reed, and during his twenties in California, he tapped into revolving farm employment—working row crops, driving trucks, building fences and a host of other ag-related jobs. The dog business stemmed directly from farm work.

Reed dealt with livestock on many of the operations he frequented, and inevitably, extensive rat presence. In 2008, with a female feist puppy, Holy Molé, at his heels, Reed was cleaning a chicken coop when a rat jumped out and was instantly snagged by Holy Molé. Watching the young terrier shake the life from the rat, Reed’s mind pivoted to possibility. “When I saw her catch I was transported in a flash to some primitive, original space. It was like everything else just disappeared around me.”

“That was the moment and it all took off from right there. Rats are a horrible, constant problem on farms and orchards, and I started slowly gathering together a team of dogs to go after rats. I contracted and caught gophers as well, and that was a great way to let the dogs develop skills.”

Stone-Cold Killer

Training is a function of proper care, according to Reed. “You’ve got to provide a dog with experience and time. They’ve got to be on location to learn not to bother cats, chickens, turkeys, goats, cattle, or whatever livestock might be on a farm. If I have a pup that’s a good dog, it’ll be a prime hunter by two or three years old.”

“Hunting is a combination of art and science,” he continues. “You know when a dog is on a fresh or old scent. It might be the bark or it may be which dog chimes in. How hot is a rat running? You work with good dogs and they’ll tell you.”

A superior dog has a basic checklist of characteristics, Reed explains. One facet is location—the ability to find rats in a wall, under manure, or in a hay bale. Another key is a drive to kill, combined with a lack of fear of rat bites. In addition, a hard-driving motor is required to work in intense heat and on multiple days. And the most significant factor? The intelligence to work within the structure of Reed’s pack, the Mongrol Hoard—a name slyly misspelled as homage to the ravaging capacity of Genghis Khan’s Mongol Horde.

Reed typically runs four dogs (sometimes more for heavy rat infestations) chosen to match a particular farm location or structure. Each dog fills a separate slot on the team: locator, runner, tight-spacer (8 lb. Peanut), sight hound, and stone-cold killer. “It takes several years to set up an ideal team. Every dog has a role, but you’ve got to have one dog in the bunch that will never, never let a rat go once it’s touched, and that’s the stone-cold killer. It’s not a screamer or yipper when a rat bites, and it just gets angrier and kills with all the more ferocity.”

Better than anyone, Reed, 38, understands the necessity of a finely-honed dog team in tackling rat problems or infestations. Years of running the Hoard and observing rats at close quarters have propelled Reed toward a dual-perspective: “My outlook on rats is best summed by respect and hate. Maybe I hate them because of how much I respect them as crazy survivors you can’t get rid of. I’ve seen wild things on farms like rats chewing on live cows. I’ve seen a brand new, high-dollar barn’s cement floor cave in because the rats dug out below the foundation. Knowing how hard the farmer worked to afford the floor, only to have it destroyed—that tells you something about the power of rats.”

Hysteria

Reed has unleashed the Hoard at ag locations of all sizes, ranging from huge dairy farms with 10,000 cows, to poultry operations with a 1 million birds, to back yard urban farms with less than an acre of land. Predominantly, he is contacted by small producers possessing a recipe for rats: “grain, feed and animals.”

Once a farm location is keyed in, Reed bells each dog (cutting down on mishaps due to livestock surprises) and loads the Hoard into custom-built dog boxes inside a four-door car. In the outdoors, the dogs adhere to a hierarchy, but in the confinement of a vehicle, separation is necessary. “Usually, even before we get there, I’ll know how many rats we’re up against just from the person’s description of the farm,” he explains. “Almost always, we’re dealing with Norway rats, not roof rats, and frankly, even with farmers, nothing causes reactions like rats. In my experience, rats cause more disgust and apprehension than anything else. Snakes cause fear, but rats bring out real hysteria, especially when present in large numbers.”

“Somebody sees rat poop and is positive they’ve got a million rats in the farm yard. That’s just not the case…but there are times when we’re talking about hundreds of rats, and it can really get crazy.”

Rat populations relate to several base causes, according to Reed’s observation: feed, infrastructure and emergency circumstances. “Aging infrastructure and access to feed are rat magnets. Maybe it’s a struggling dairy farmer who doesn’t have the money to repair a cement floor or pay for proper maintenance, and the result is a rat haven. Or, let’s say a grandfather dies and the farm goes to s*** for two years. By the time somebody comes in and buys the place or the family gets it back to full function, there may be a huge rat problem waiting.”

The Hunt

Pulling onto a farm driveway, the dogs are dialed into the process and go wild in the tight vehicle, howling as bodies vibrate, muscles twitch and bells jingle in expectation of the fight ahead. “They read my vibe and feel my own anticipation and feed off it. They go totally crazy.”

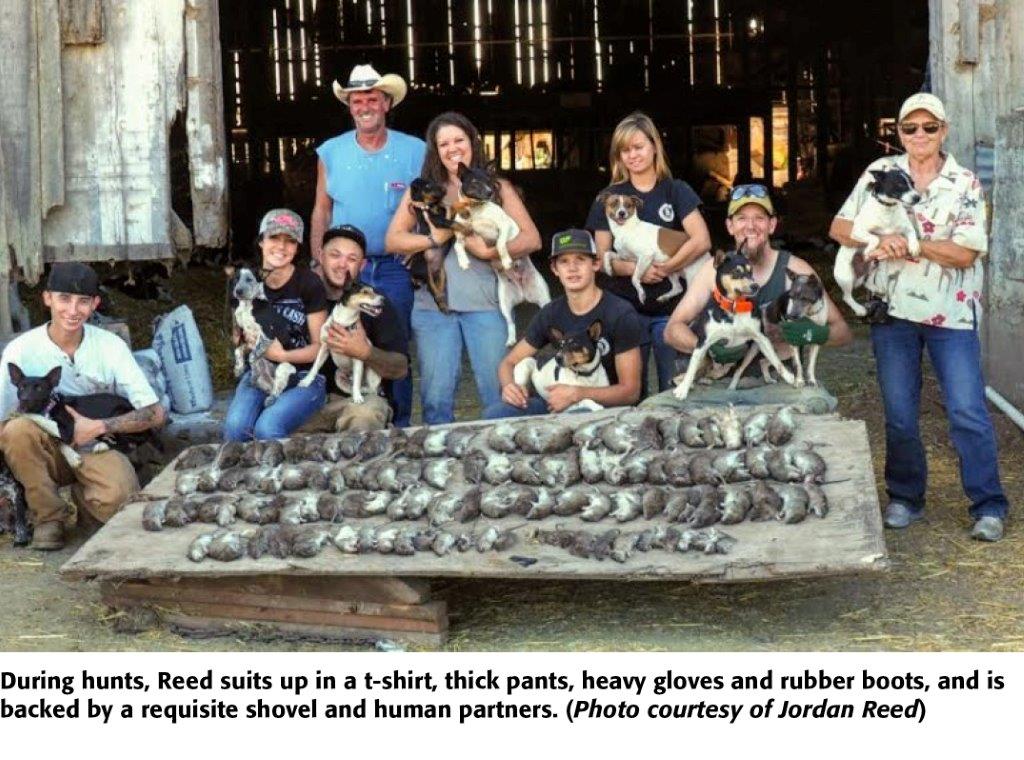

During hunts, Reed suits up in a t-shirt, thick pants, heavy gloves and rubber boots, and is backed by a requisite shovel and human partners. “There is a ton of labor because this is kind of like farm cleanup with dogs. You can argue and refuse to clean something when your missus has had enough, but when I show up, I’m about to tell you what shed to clean and what pile of junk to throw away. I insist on having a farm owner present when we hunt, because things get destroyed.”

Once the farm location has been properly scouted, the baying Hoard is released and the madness begins. Barking, snarling, crying, digging, biting walls, dragging away tires, or using snouts to bulldoze impediments, the pack begins to dislodge rats from cover. Reed digs directly into burrows with a shovel, or flushes holes with a water hose, or inserts an exhaust hose connected to a repurposed chainsaw that serves as smoker—any means necessary to get the rats in motion. “We do the big physical work to make the rats accessible,” Reed explains. “Maybe we clean, turn big things over, use a carjack to lift things or insert cinder blocks. Anything to get the dogs closer to the rats.”

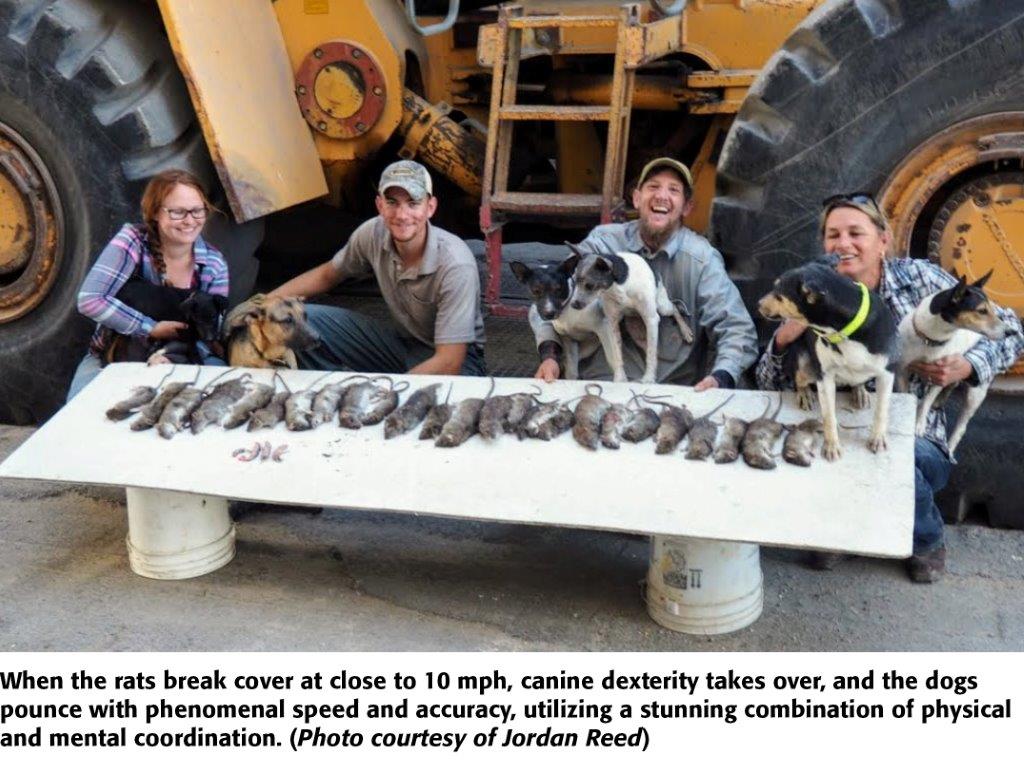

When the rats break cover at close to 10 mph, canine dexterity takes over, and the dogs pounce with phenomenal speed and accuracy, utilizing a stunning combination of physical and mental coordination.

Kaity McCracken, 30, is a long-time friend and hunting partner of Reed’s in Sebastopol, Calif., and at least once a year, the duo hits a farm together. “The dogs lose their minds when we pull up to a farm to hunt,” McCracken says. “When we start, sometimes we’ll have three or four people waiting at different burrow escape holes or routes. After we flush a hole, the rats come busting out, and you have to holler, ‘Over here’ or ‘Get it, get it’ as loudly and as excitedly as you can. The dogs get to scrambling right over. When the rats fly out of the holes, it’s all hands on deck, and the dogs go crazy. They dispatch one and move on to the next. Some of the dogs stick close to the holes, and others wait for the runners.”

The dexterity of the Hoard is best captured in Good Golly Girl, now deceased, but a feist that maintains a grip on Reed’s heart: “She was a big dog and incredibly smart…probably the smartest dog I’ve had,” he recalls. “When a rat runs and goes through a fence, the chasing dog runs up to the fence and tries to go through, barking while the rat escapes, but Good Golly remembered all the gates. When a rat hit a fence, she’d hit the gate. She’d work solo, 30 yards off us on an escaped rat and bring it back dead—so impressive.”

Good Golly’s coordination was remarkable, as described by Reed: “She could be at a full run and reach down to pick up a rat alive by the scruff of the neck with her two canine teeth, almost in a delicate way. Then she’d carry it around until she wanted to kill it. Incredible coordination.”

The dogs kill the rodents by shaking or biting. Each pack member has a slightly unique style, but trimmed down, dogs are either “shakers or crunchers.” Hunts last three to four hours, and produce a kill total on the low end from 5-10 rats—or the high end reaching into the hundreds: “I’d generally say 50 rats is a lot, but the most we ever caught was 292 in one session,” Reed recalls.

Freight Trains and Water Balloons

Cory Miller is a frequent hunting partner of Reed’s, and was in attendance when the Hoard racked up 292 rats in just several hours. “I’ve hunted everything from private chicken coops to huge dairies with Jordan, and no matter the location, there is a quiet intensity to Jordan. When you hunt with him you can’t help but get into it because he’s into it, and he’s on a shovel—no standing around.”

Miller, 39, trains dogs in Thurston County, Wash., and understands the primal nature of hunting. He uses a feist as a lead dog to flush game during falcon hunts. “I fly different birds depending on the game. One is hot on pheasants and squirrels, another is hot for rabbits. It depends on where we’re at and what kind of cover is present, but I’ll pick the bird to match. It’ll get your blood going when you see a falcon drop out of the air and crush something. That’s the same feeling Jordan has when his dogs pound a rat.”

“When dogs hit rats, there is no subtlety and no romance,” Miller continues. “The dogs go from frantic to extreme focus in a millisecond. Watching a dog hit a rat is like watching a freight train hit a water balloon.”

“Jordan is intense and all his dogs are intense,” Miller adds, “from tiny Peanut to big girl Squeakers. It’s one and the same. It just happens. No caution and no planning. A rat moves; a rat dies; end of story.”

Risk and Danger

After a hunting session ends with bags of dead rats, Reed calls several friends involved in falconry interested in feed sacks packed with rats. “These guys feed their birds natural foods, and to buy quail and rabbits, or store-bought rats, is very expensive. They’ll come to the farm or meet me at a rest stop and gladly take the rats. Or I know guys who grind them for coyote bait, but whenever there is a question of poison, we take the rats to the landfill.”

Norway rats average a half-pound in weight, and pack a hefty bite. (Reed has been nailed twice.) Despite the dogs’ speed and craft, they are consistently bitten, often with severe injury (front leg bites have opened arteries). Bites frequently occur when two dogs simultaneously grab a rat, negating the ability of either dog to shake; the dog closest to the rat’s mouth is subject to a deep bite. Ears, cheeks, nose, sinus cavity, gums, tongue—the bites usually draw infection and require medication. “The dogs get really sore mouths,” Reed describes. “Anytime they catch over 20 rats, they’re going to have heavy bites to the face, but over 100 rats and the dogs really get torn up. Certainly, the more experienced dogs get bit less, but they all get bit.”

Despite the issues posed by rat bites, the greater risk is found across the general farm environment, and Reed doesn’t sugarcoat the danger. “Things happen fast and furious and things get intense. I’ve had hay bales fall on dogs, and dogs stomped on by cows. I’ve had a dog electrocuted from faulty wiring on the barn roof against a gutter that fell down and touched a piece of sheet metal; my dog ran behind the metal. Another time, a guy had an air gun and shot: The pellet hit two rats, continued through a pallet, and hit my dog in the liver—killed him. No more guns on hunts, never.”

Lost and Forgotten Skill

Every spring, Reed hits the road on the sheep shearing circuit with the Hoard in tow, traveling across the U.S. The dogs help him push sheep through handling facilities, occasionally hunt rats on days off, and stay in peak shape. “I’ve got high-performance dogs, extremely high-energy. I’ll run them with a car or mountain bike, and they just don’t get tired. Maybe every four or five days, we’ll hit a farm and catch rats. Even when they’re on a farm and I’m working, they’re very well-behaved and nobody minds when they crawl under the barn to drag out a rat.”

Rat hunting with trained terrier packs was historically common in Europe, but the practice has all but died in the U.S., except for the Mongrol Hoard. “I’m just a regular guy that drives dogs around in his car and spend time on farms, but I’m doing something that has gotten lost, although it’s something that used to not be unusual because it was valuable—and still is.”

Under Reed’s tutelage, McCracken has trained her own unique band of rat-hunting dogs, including a 13-year-old Great Dane, as well as a 53-lb. shepherd mix. “Some people think only a certain kind of dog can do this, but not Jordan. He’ll find a job for a dog no matter the size, breed or age. If a dog is willing to work, Jordan is all about it.”

Employed in the sports industry, McCracken also has a goat milk business on the side, and works her dogs on her property in Sonoma County: “I’d say 99% of rat hunting is knowing how your dogs work together and knowing who is going to be good at what.”

At first blush, observers might assume any dog is capable of catching rodents on a farm, but Reed says the Hoard, as a whole, vastly outweighs its component parts. “Some guys have a dog that catches rats here and there, but they don’t realize what goes on with high-performance hunting dogs that perform consistently under every imaginable condition. Also, you have to know about the construction of farm buildings and how they are utilized by rats, and you have to know hunting dogs and how all the puzzle pieces fit together. I guarantee: You can’t just get some dogs and go kill rats.”

“There’s a heavy amount of learning involved, and very few people want to make the effort to learn how this is done. They all love the fun part—watching or chasing, but nobody wants to do the work,” he adds. “I can give you my own dogs and put you on a farm and let you catch as many rats as you can. I’ll go the next day to the same spot with my dogs and catch more rats than you.”

Reed’s words are backed by fact, Miller says. “Jordan knows how to take dogs that have the natural drive and ability to do a job, and put them in an environment where they have the opportunity to be successful. I hunt with lots of guys who are eager to brag, but Jordan is the opposite. Nothing but plain talk and he means exactly what he says. He picks up a shovel, starts throwing things around, and s*** dies.”

Blood and Dirt

With Reed’s recent move from California to Oregon’s timber country, the Hoard relies on coordinated road trips for rat hunting. However, Josephine County has nutria rat presence, and the Hoard has taken to nutria hunting without skipping a beat, explains Reed. “Nutria are an invasive species, just like the Norway rat, and both do major damage to agriculture. I’m using my same dogs to kill another invasive species and there are no restrictions or permits required.”

Reed’s passion for feists and terrier-type dogs runs deep into his core. “Heart and soul,” McCracken emphasizes. “These dogs are part of who Jordan is.”

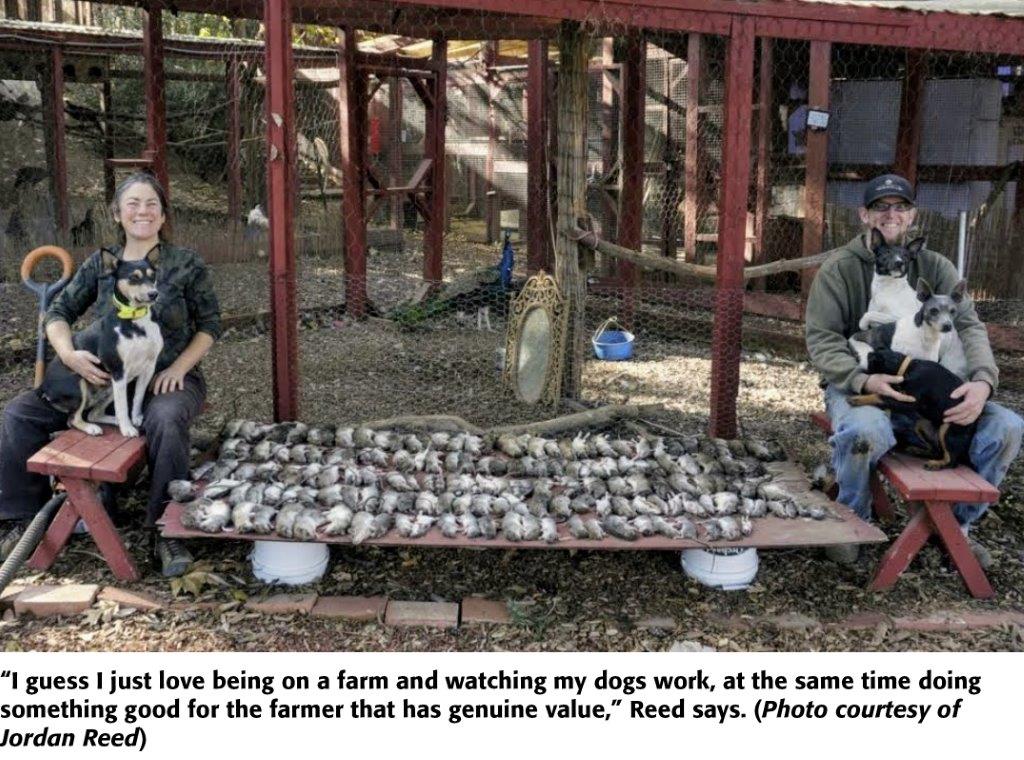

The Hoard is Reed’s shadow, Miller concurs: “He loves hunting those dogs like he loves breathing. No exaggeration. Jordan is one of those rare people lucky enough to find something he’s really passionate about and gets to share with others, at the same time benefitting his dogs, himself, and farmers.”

When dirt flies and blood sprays, and the Hoard springs into action, Reed is the lead dog, in the middle of a team of his labor and creation. “I guess I just love being on a farm and watching my dogs work, at the same time doing something good for the farmer that has genuine value. I’ll hunt with these dogs forever because I’m alive in the moment and there’s nothing like that feeling. Everything else disappears.”

In the meantime, the Mongrol Hoard waits like a coiled spring, watching Reed’s every move with pleading eyes, hoping he picks up a shovel and sets the madness in motion. “Nothing like it,” he grins. “Minute by minute, hunting rats on a farm is about the most action you can possibly imagine with hunting dogs.”

For more, see:

Corn Maverick: Cracking the Mystery of 60-Inch Rows

Descent Into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

Blood And Dirt: A Farmer's 30-Year Fight With The Feds

American Farmer Snuffed Out Saddam Hussein

Against All Odds: Farmer Survives Epic Ordeal

Future Shock: Farmers Exposed By US-China Long Game

Wild Pig Wars: Controversy Over Hunting, Trapping in Missouri

Agriculture's Darkest Fraud Hidden Under Dirt and Lies

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer