The Great Shame: Mississippi Delta 2019 Flood of Hell and High Water

Weary to the bone, Smith Stoner shut down his picker and stared into the pitch black of 3 a.m. darkness, separated from the finish line by a lone 75 acres of cotton, the last remnant of harvest. With the rest of his fields either binned or baled, Stoner should have been close to satisfaction. Instead, the Yazoo County producer was bothered by a dark premonition as he descended the picker ladder and felt the touch of raindrops—the first trickle of a cataclysm, which would consume an entire region of the Mississippi Delta, yet go almost entirely unrecognized by national media. “Oct. 16, 2018, was a day I’ll never forget as long as I live,” he recalls. “That was the first sign of water that fell for months later like something out of the Bible, and all you could do was watch your land and your livelihood drown, and the whole damn time the water wasn’t the worst part of the flood; the worst part was that it never had to be.”

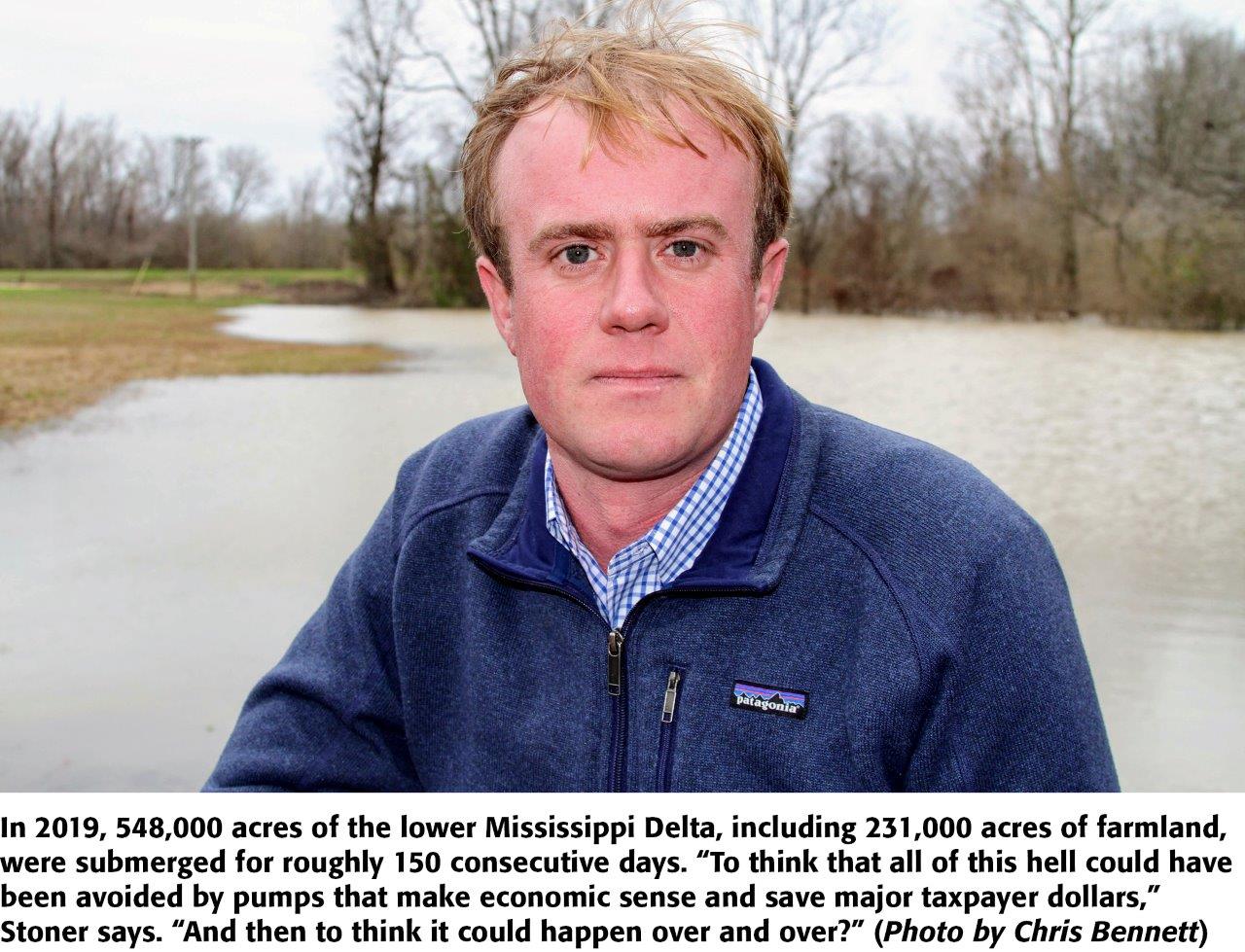

Five months of ruin forgotten by all. In what ranks as one of the most heavily ignored and needless catastrophes in recent U.S. history, 548,000 acres of the lower Mississippi Delta, including 231,000 acres of farmland, were silently swallowed in 2019 and submerged for roughly 150 consecutive days. Multiple deaths, 686 homes swamped, three highways under water, and 20,000 people pleading for a modicum of common sense from the federal government, along with a host of Delta farmers unable to plant a single seed in 2019. An acreage zero. Nada. Heaping insult on injury, only a decade prior the source of salvation in the form of relief pumps had been vetoed by federal bureaucrats and deemed a liability by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The near-guarantee of the 2019 flood was the worst kept backwater secret of the past 45 years, i.e., it essentially was openly predicted by every South Delta landowner since the 1970s. Mississippi farmers have clawed, kicked and screamed at the feds for decades, warning of a cataclysm around the corner, and in 2019, the predictions were toe-tagged with a vengeance which left a region in tatters, and forced EPA officials to reckon with a policy train wreck. “Let me tell you about a flood that nobody seems to want to hear about,” Stoner says. “Let me tell you about hell.”

Hell and High Water

Stoner grows 2,800 acres of corn, cotton and soybeans in the heart of the South Mississippi Delta, an hour’s drive north of Vicksburg, near Holly Bluff, roughly 30 miles east of the Mississippi River. During the final months of 2018, October to December, Stoner watched as the skies bled an inordinate amount of water, and forced his gin to operate an improvised system of triage. All cotton picked prior to Oct. 15 was given priority; it was dry. All cotton harvested after Oct. 15 received second-tier status; it was wet. “That was a marker of what was to come,” he recalls. “All this rain was steady falling and we eventually got our last 75 acres of cotton out, but couldn’t do a lick of field work. It felt strange, but still I didn’t comprehend the flood of floods was just around the bend.”

Even as rain continued into January 2019, Stoner focused on seed choices, planting dates, an operating loan, commodity prices—and all the pre-season noise associated with farming. But, the 31-year-old producer couldn’t shake a nagging sensation of something or someone moving onto his flank—the odd feeling of staring over the shoulder and seeing nothing, yet sensing presence. “At that point, I still thought we’d be OK, but I couldn’t get rid of the thought that something was way off.”

In February, the rains came all the harder, and the specter of flooding danced to center stage, transitioning from rumor and possibility into hard reality. Cotton prices and China tariffs were reduced to matters of zero relevance: The South Delta was going under water, and the only question remaining: How deep?

As March rolled in, and more rain rolled down, Stoner scrounged for hope. He typically plants corn in mid-month, but in 2019, March was a sputtering chain of stop-gap measures, from driving equipment to high ground to building levees around the shop, all while his farmland disappeared by the day. Maybe corn pushed to April, planted roughshod on no till ground behind cotton stalks, and then all remaining acreage shifted to cotton? “I was still lying to myself that I could get half my acreage planted. No way: I was trapped along with most everybody else.”

Indeed. The South Delta was filling fast, bloated from incessant rain, and by April, hundreds of farmers were in last-stand mode, piling makeshift levees higher and using relift pumps to protect property, all the while desperate for a planting window. Yet, for many growers, the efforts equated with a rearrangement of the deck chairs on the Titanic. The crop season was literally over before it started. On April 15, Stoner stirred at 3 a.m., unable to sleep and desperate to parse through financial numbers, hoping to salvage a miracle. Against the pane of his office window, he heard cruel, telltale taps: Once again, it was raining.

Build the Pumps

Thirty miles southwest of Stoner, outside the tiny community of Onward, Victoria Darden, 28, watched water climb onto and over her 1,100 acres of farmland, and scrambled with her father, Randy, 73, to move equipment to high ground. “The water started backing up in February, but I didn’t immediately realize it wasn’t going away,” she says. “We watched the water creep up, but we’re farmers, and supposed to be the eternal optimists. Right? I mean, how bad could it get?”

All her life, Darden had heard Delta flood stories, particularly about 1973 and 40 days of travail, but none of the accounts prepared her emotionally for 2019. Darden’s farm was about to be devoured, and her tiny remaining high ground and home place were about to become an isolated island—surrounded on all sides by water up to 8’ deep for five months.

“It was emotional torture to feel so alone,” Darden recounts. “I watched the strain on my daddy because he couldn’t plant a crop for the first time in his life, and he also recognized what I couldn’t—the devastation still to come. And all such a waste because no matter how many times we tried to cut through red tape or tell the government what was going to happen, they wouldn’t listen to the only real solution: Build the pumps.”

In Harm’s Way

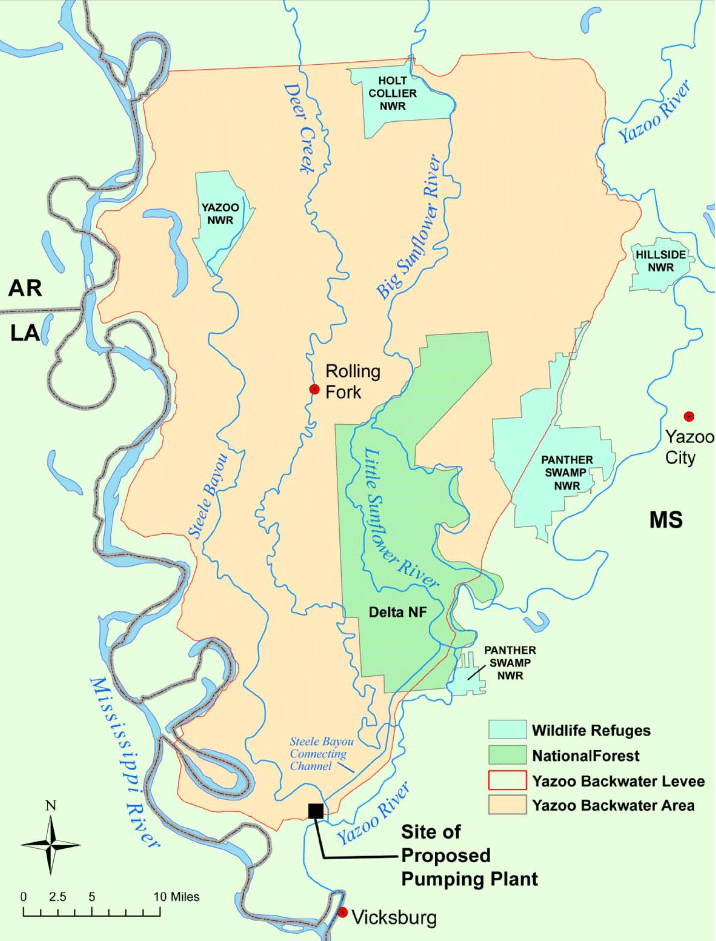

The entire Delta (2.62 million acres) is a flood-prone region, but the South Delta (926,000 acres), tucked between the Mississippi and Yazoo rivers is a receptacle. Bluntly stated, Stoner and Darden farm in a South Delta basin with a single drain—the four-gated Steele Bayou Drainage Structure in Issaquena County, 10 miles north of Vicksburg.

The Delta is protected by a network of levees along the Mississippi River which prevent it from flooding the 200-mile-long region. Additionally, the South Delta contains backwater levees that funnel all greater Delta drainage through the Steele Bayou floodgates (built in 1969), and into the Mississippi River at Vicksburg. However, when the Mississippi River gets high, it attempts to back into the South Delta, and in response, the Corps of Engineers closes the Steele Bayou floodgates to ensure the South Delta isn’t inundated by the rising Mississippi River.

The levee and drainage system is both servant and master: It protects the South Delta and holds it prisoner. When the floodgates are closed, the rainfall and drainage generated across 2.62 million acres of greater Delta land all flows south and is trapped because the outlet is blocked when the Mississippi River rises to flood stage. Simply, the drain is clogged. In 2019, the backwater reached 98.2’, resulting in a historic flooding event—the worst since the backwater levee and drainage structure system was completed in 1978. The vista from fabled Highway 61 was surreal, almost pulled from the pages of water-world fiction: A drive on 61 south of Rolling Fork revealed a surreal lake stretching toward the horizon. A massive chunk of the South Delta had been swallowed, evidenced by 548,000 acres of land underwater for five months, including 231,000 acres of cropland which was never planted in 2019.

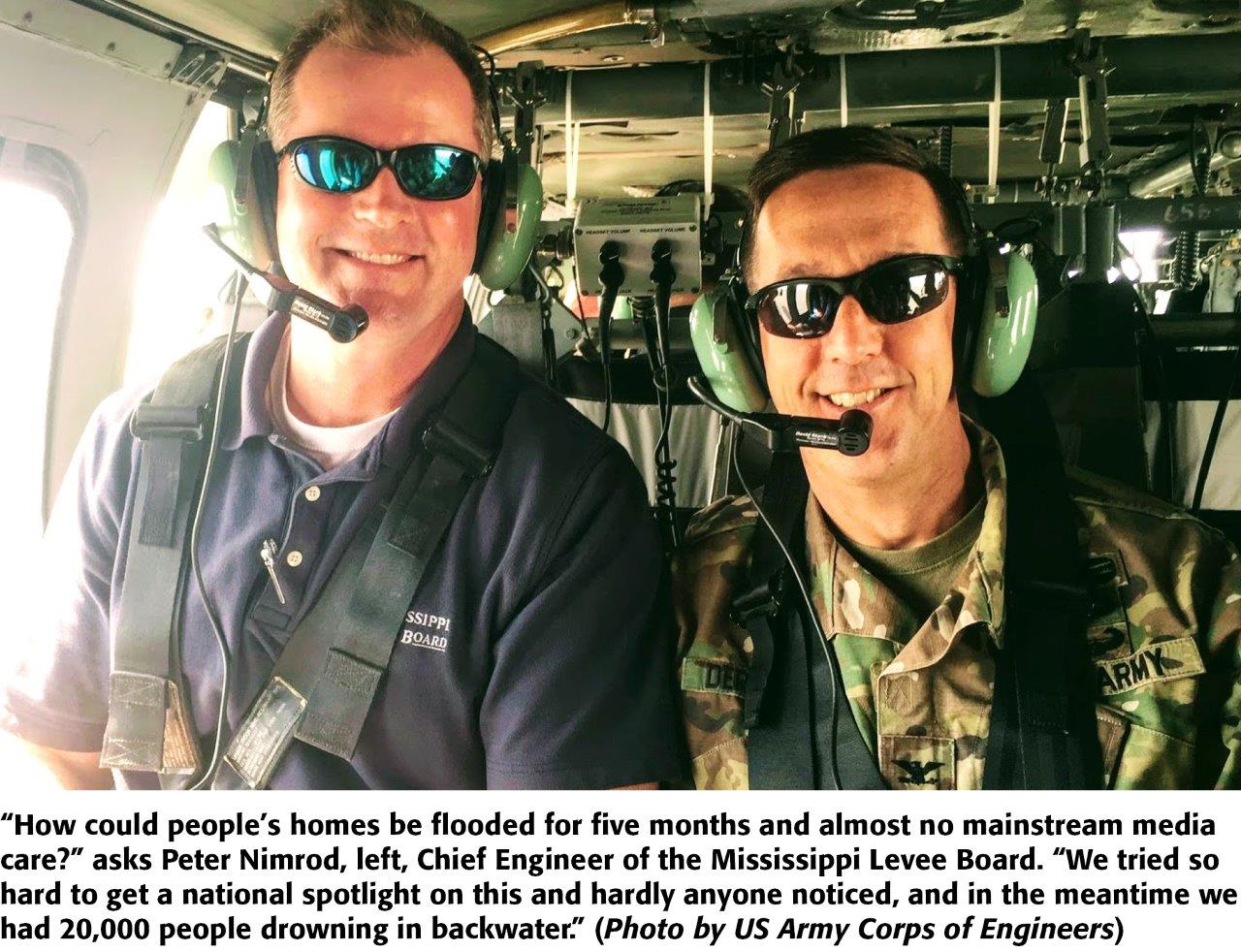

“Life stopped for all walks of life,” describes Peter Nimrod, Chief Engineer of the Mississippi Levee Board. “Everyone: white, black, farmers, farm hands, and people not related to agriculture. What happens to an economy when people can’t go to work, the grocery store, school, restaurants or church?”

“How could people’s homes be flooded for five months and almost no mainstream media care?” he asks. “We tried so hard to get a national spotlight on this and hardly anyone noticed, and in the meantime we had 20,000 people drowning in backwater.”

The solution has always been in plain sight, Nimrod says, in the form of a pumping system to take water over the backwater levee and into the river at Vicksburg. Pumps would ensure manageable control of future floods, he insists: “There’s only one solution and everyone knows it: pumps. We’ve been in harm’s way for no good reason.”

During the 2019 flood, Nimrod and his Levee Board colleagues took advantage of a tiny airport on the Louisiana side of the Mississippi River to monitor flood conditions. Each time Nimrod took flight, the stark contrast between opposite sides of the river was clear. “I could see all the Louisiana farmland rowed up in March and guys planting corn. We’d fly across to Mississippi and see 3’ of water covering farmland.”

From a bird’s-eye view, Nimrod was observing bone-dry Louisiana farmland at an 88’ elevation and flooded Mississippi farmland at a 94’ elevation. The difference? Louisiana (and Arkansas) has what the South Delta craves—a relief pumping system.

Collateral Damage

In 2008, EPA vetoed South Delta pumps, citing environmental concerns over wetlands destruction. By bureaucratic fiat, an entire region was prevented from obtaining permanent relief and left perpetually exposed to the whims of weather. EPA had spoken; no pumps.

Significantly, in the decade following the veto, from 2008-2018, the South Delta sustained $372 million in consistent flood damage. In 2007, one year prior to the veto, the pump construction was estimated at $220 million. “In less than a decade, we could have justified the cost and saved $152 million, and I’m not even factoring in 2019 costs yet; those will be astronomical,” Nimrod says. “The pumps were and are a complete no-brainer.”

He recalls EPA officials visiting Vicksburg prior to the veto. “The EPA at the administrative level was so radical in 2008, and they came to Vicksburg as part of a public hearing process to basically check off some boxes. We had 500 people show up to be heard, and we invited the EPA reps to come back to see what was just a backwater flood in 2008—not even a catastrophe: ‘Please come look when you leave this meeting tonight and drive 10 minutes north to take a look. Come to the backwater.’ They left and said they didn’t have time, and vetoed the project in August. Unbelievable.”

The pumping denial by EPA is a classic case of farmland as collateral damage due to misguided environmental policy, Nimrod says. “Environmental extremism played a huge role. Environmental groups, staffed by people with no idea what the Delta even looks like, had a huge role in influencing EPA. You really care about the environment? Come look at our decimated wildlife populations and dead trees. Get out of your office and come look at a place that won’t completely recover for years.”

The Big Zero

By June, Stoner was behind a fortress of sandbags and had managed to get a small portion of hilly ground planted in cotton, but 2,000 acres remained underwater and was a total planting loss. A few dry ridges poked above the lake-like fields, but were entirely inaccessible to equipment. The Yazoo and Sunflower rivers, Deer and Silver creeks, and a network of sloughs were in open rebellion, spitting excess across the land.

Stoner’s ground had disappeared, but his loans remained in full sight. Tears, anger, despair, grit—Stoner rolled through farming emotions hidden from the public eye, often driving alone on high roads and hoping for an answer, with the cold math of fixed expenses riding shotgun. “Guys have rolled debt, deferred notes, anything to go again. It’s like a nightmare we never dreamed has suddenly become reality. We can’t even plant a crop? The public thinks crop insurance pays everything and you’re good to go, but you lose and lose. One bad crop and you can be done forever, and we’ve got lots of guys that planted zero. Zero.”

“We are prisoners of politically correct, environmental overkill, and at the same time we’re surrounded by starving deer and every other kind of animal, and trees that will all die. There’s a whole society of people besides farmers trapped by this water, and small businesses hurt way worse than farmers, but you’d never know that from the news. Watch what happens if they keep refusing to allow pumps: You’ll see the South Delta go into trees and towns fold, but maybe that’s what EPA wanted all along.”

Southwest of Stoner, Darden’s operation had turned into a makeshift island surrounded by the Steele and Black bayous, and there was no hope left for a single 2019 seed—fish literally swam the furrows. Until the final week of July, Darden and her father boated 20 minutes each day on a one-way ride to reach the dry ground of a neighbor’s property, easing through a labyrinth of debris and timber, a pall of dead wildlife, and the constant presence of nauseous odors. “No smell in the world like dead deer carcasses in a flood,” she says. “Maybe the Sierra Club and the Audubon Society should come breathe it in, because no amount of pictures can duplicate the smells of flood decay.”

“We don’t need the government to rush in and save us after a flood; we can manage. We need the government to fix a manmade problem before the flood,” she continues. “Red tape, environmental extremism, lack of reason...it’s all right here. All it takes is for people to get the facts and then they quickly get behind us.”

No-Brainer

The facts, echoes Nimrod, will carry the day and bring a pumping system to the South Delta. The flood of 2019 has spurred heavyweight, bipartisan support for pumps at all levels of Mississippi politics, and pushed fence-riding organizations into pump support, he explains. “The same talking points from the same extremists no longer work, because they can’t control the narrative anymore. All the claims about destruction of 200,000 acres of wetlands are entirely false, and people are now aware of what is really going on.”

The possibility for a pumping system has gained new life in tandem with administration change at EPA, according to Nimrod. On March 18, 2019, Nimrod invited new EPA Region 4 Administrator Mary Walker to see South Delta flood damage, and the result was a far cry from 2008. “She actually made the effort to come here. We flew her around the backwater area in a helicopter when the water was at 97.2 feet.”

Nimrod sat beside Walker, and watched as the EPA administrator shook her head in disbelief. “She saw it all. Homes, highways, farmland, all underwater. She saw what her EPA had vetoed, and nobody had even cared enough to come visit from the previous Bush or Obama administrations.”

The Corps of Engineers recently has gone over new environmental data with EPA related to pump presence. “The Corps is about to submit a modified project and EPA is going to take another look and hopefully issue a permit,” Nimrod says. “Things look positive in 2020. Farmers and the people of the South Delta have some light at the end of the tunnel.”

The four-year proposal allows for a single pumping station beside the Steele Bayou floodgates and consists of 12 pumps with a total capacity of 14,000 cubic feet per second. At present, the station would cost $380 million. “It’s such a no-brainer,” Nimrod says. “From 2008 to 2012, $372 million U.S. taxpayer dollars were spent on flood damage here. Build the station and end the taxpayer expenditure once and for all.”

The proposal, Nimrod contends, is a balance of economics and environment with $190 million for pump costs and $190 million for reforestation efforts ($380 million total). Basically, as compared to pumps in other areas, the South Delta station will leave water in the proverbial ditch, and concedes a portion of flooded ground. The pumps won’t be turned on until 87’, and that translates to 216,000 South Delta acres underwater. “That’s still not good enough for some environmentalists, but we can live with it and manage,” Nimrod says.

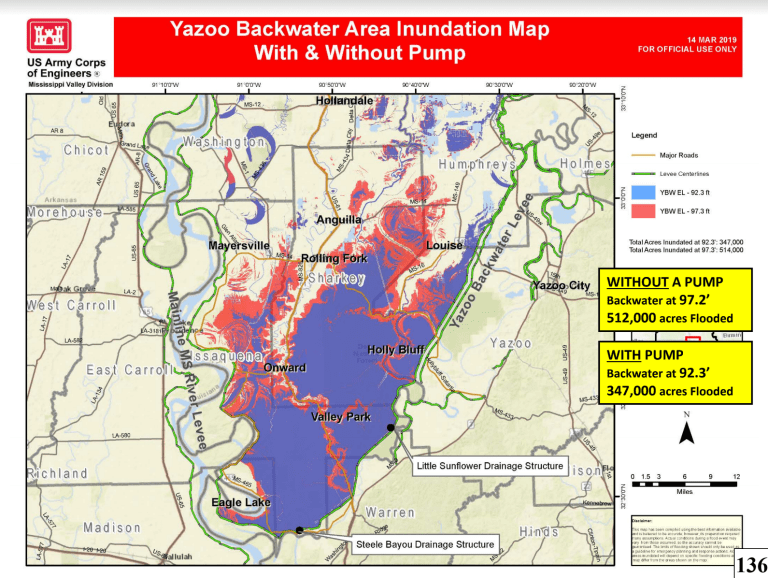

If EPA greenlights the project in 2020, the pumps will require four years of construction, a considerable window of time, but the alternative is permanent exposure. If the South Delta had been equipped with a pumping station in 2019, Nimrod estimates, backwater levels would have hit 92.5’, rather than the devastating 98.2’. “It would have been a difference of night and day, and the flood would have been manageable because we would have lost zero homes, no highways and 200,000 less acres of land, including 122,000 less acres of cropland flooded.

Further, water pumped out of the South Delta will be an inconsequential addition to the Mississippi River already flowing at 2 million cubic feet per second. “People think when we have 14,000 cubic feet per second going into Yazoo River, and then 10 miles downstream it hits the Mississippi River at Vicksburg, there’s going to be a 10’ wall of water and drown everyone downstream. It’s actually a miniscule addition, and the Corps models show a worst-case scenario where pumps would add about 2” of water to the Mississippi River at Vicksburg. That is nothing.”

“We’re Not Leaving”

When the waters finally receded in August, a giant lake was replaced with a desert. Stoner, Darden, and most South Delta farmers were left with a reeking mess of decay, washouts, ruined roads, dead wildlife, ditch cleaning, culvert repair, debris removal, and field work—just for starters.

“To think that all of this hell could have been avoided by pumps that make economic sense and save major taxpayer dollars,” Stoner concludes. “And then to think it could happen over and over?”

It will happen again, Darden emphasizes—without the pumps. “I would love to have a crop next year, but I don’t know if going back to normal will ever be an option. Do we ever get the pumps? The mood around here has been heavy with hostility. Why? Because we’ve been forgotten,” she adds. “But we’re not sitting back afraid to speak out, and we’re not leaving. You don’t leave a legacy.”

For more, see:

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Descent Into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

Corn Maverick: Cracking the Mystery of 60-Inch Rows

Blood And Dirt: A Farmer's 30-Year Fight With The Feds

American Farmer Snuffed Out Saddam Hussein

Against All Odds: Farmer Survives Epic Ordeal

Future Shock: Farmers Exposed By US-China Long Game

Wild Pig Wars: Controversy Over Hunting, Trapping in Missouri

Agriculture's Darkest Fraud Hidden Under Dirt and Lies

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer