Soybean Stunner: How a Con Artist Pulled the Greatest Agriculture Heist in History

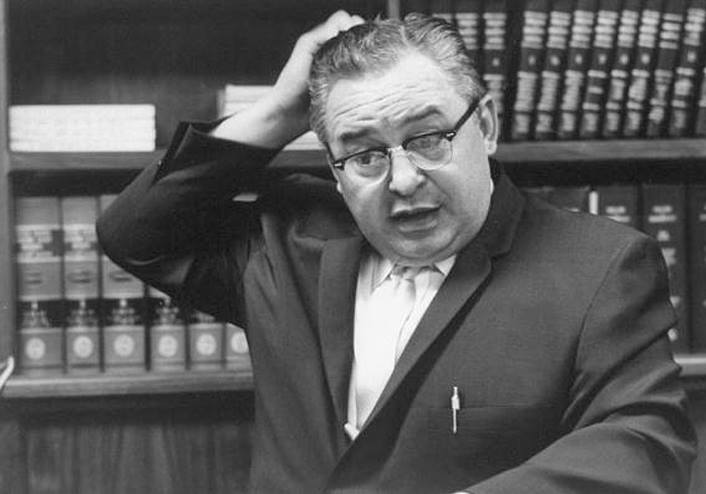

Beware the man who eats soybeans and shi** gold. In the pantheon of agriculture’s notorious con artists, one hustler reigns supreme—Anthony “Tino” De Angelis, the Salad Oil King.

With soybeans as his wheelhorse, De Angelis stole over $1 billion at today’s currency rates, shook Wall Street to its core, dragged American Express to the brink, humiliated big banking, embarrased USDA, ushered in the rise of Warren Buffet, and flaunted a dizzying chain of Ponzi pyramids.

For almost two decades, De Angelis’ hand touched more U.S. soybeans than anyone on the planet, as he pulled the levers on an incredible succession of agriculture crimes involving ghost tanks, rancid product, fake receipts, market manipulation, and a reptilian ability to shed blame.

“I was the Salad Oil King,” crowed De Angelis.

Truer words never spoken. Welcome to the king’s twisted tale.

Commodity Heaven and Hell

In February 1915, one of the most notorious criminals in U.S. history, Frank James, the last of the James Gang and elder brother of Jessie James, passed away at his farm in Kearney, Missouri. On cue, nine months later in November 1915, Anthony “Tino” De Angelis was born 1,200 miles east in Harlem, New York City. Out with the old, in with the new.

At 16 years young, De Angelis dropped out of school in 1931 and borrowed $500 from his rail worker father to invest in a candy store, a risky play during the heart of the Great Depression. Adios to the cash when the candy store crashed, but the loss highlighted the moxie of a NYC teenager intent on making the big time.

De Angelis bounced to a bottom-dweller job at a meat and fish market, but gained the manager’s hat within three short years, testament to his genuine business promise and high intellect. The fish market stint was followed by a foreman’s role at a hog processing facility in the Bronx. In 1938, with experience and a nest egg beneath his mattress, De Angelis invested in M&D Cutters, a New York butchery, and hauled in $300,000 three years later.

Hidden behind bland physical features—a diminutive 5’5” in height and plump as a boardinghouse cat, hair combed directly back, horn-rimmed glasses, pearl-gray neckties, no jewelry or outward flash—ambition’s fire roared in De Angelis. At the close of World War ll, he started a packing company to fill insatiable foreign market holes, and inked a 1947 deal with the Yugoslavian government for $1 million in lard. When the Yugoslavians sued De Angelis for delivery of spoiled product, he quickly settled with a $100,000 apology. Business acumen he possessed; business scruples he lacked.

Gaining in stature, De Angelis bought majority interest and assumed the presidency at a North Bergen, New Jersey meatpacker outfit, Adolf Gobel Co., and secured a USDA school lunch program contract to the tune of 19 million lb. of smoked meat. De Angelis delivered a measly 2 million lb.—uninspected and inedible. When USDA called him out, De Angelis skirted responsibility, blamed a mix-up, and agreed to give Uncle Sam $100,000 for the trouble. Within months, blacklisted from future federal contract bids, De Angelis was fired and Gobel went into bankruptcy.

De Angelis moved toward bigger and better. The future, as he correctly assessed, was in soy. No longer poverty peas, soybeans were commerce, and the supply of soybean oil, generally sourced from the Midwest, was outpacing domestic demand. De Angelis envisioned U.S. food-grade oil flowing to foreign countries, with his fingers on the tap.

From collapsed candy store proprietor to butcher’s assistant to meatpacker president, De Angelis’ ascent was only beginning. He was about to seize the Salad Oil throne and unleash commodity heaven and hell.

Buy High, Sell Low

In November 1955, De Angelis plunked down $500,000 on his masterstroke—Allied Crude Vegetable Oil Refining Corporation in Bayonne, N.J., 1,000 miles from the soybean blankets of the Midwest. He bought a tank farm in Bayonne—a battered petroleum storage center with roughly 150 tanks, some 50’-plus in height—and converted the facility into a soybean (and cottonseed) oil refinery.

But how could De Angelis navigate a geographic disadvantage and logistical hurdle to compete with grain stalwarts in farm country that shipped product bound for foreign ports down the convenient Mississippi River to New Orleans? According to De Angelis’ crooked calculus, location was irrelevant: All he needed was access to the middleman’s ear.

At its heart, his game plan was simple. Buy and ship unrefined soybean oil to the East Coast, process the oil, and sell for minimal profit for export via private commerce or government programs. The margin was wafer-thin, but De Angelis aimed to make up the difference in volume. Suck up the soybean oil supply with prices no one could match and chop-block Midwest competitors. It was a precarious high-wire act: Buy high and sell low.

De Angelis broke bread with exporter after exporter. He procured the individual rates paid by soybean oil producers in the Midwest and undercut them all. The Midwest brokers initially laughed at the East Coast wheeler-dealer, but by 1957, De Angelis was swimming in money. He set up roughly a dozen companies beneath Allied’s umbrella, all harnessed to the goodwill of USDA’s Food for Peace Program (FFP) providing ag commodities to needy foreign countries.

In short time, no one would mock the Salad Oil King, because behind De Angelis’ Humpty Dumpty features lurked a cross between Walter White and Genghis Khan.

Oil Floats on Water

De Angelis became the golden boy of U.S. agribusiness. Chauffeured around NYC with an ever-present, thick knot of bills in his pocket, De Angelis believed his own press. “I have a brilliant and productive mind, and I could do more for our fats and oils business than anyone else in the world. I knew, as president of Allied, that I could go out and sell all the vegetable oil that this country could ever produce.”

Feted by foreign dignitaries in Madrid, Rome, and Karachi, De Angelis doled out money and oil in unprecedented volumes, and although the feds could smell rot, they were blind to the machinations of the steal. An inner core of 22 Allied employees—handpicked and doggedly loyal—did De Angelis’ bidding and stayed mum. In return, almost all drove Cadillacs and pocketed $400 per week, in addition to frequent cash gifts, as noted in Norman Miller’s 1965 book on De Angelis’ crime spree—The Great Salad Oil Swindle. (Miller won a Pulitzer in 1964 for his newspaper coverage of De Angelis’ antics.)

With a wink, De Angelis stayed on the cusp of prosecution. When the SEC accused him of possessing a fantasy lard inventory, the government’s star witness mysteriously was stricken with laryngitis. When the IRS hit De Angels with a $1.5 million tax evasion case, he settled for a $50,000 fine up front, plus $5,000 every three months for 10 years. When USDA came knocking and charged De Angelis with stealing $1.2 million from the Food for Peace Program, he quelled the government’s anger with a $1.5 million check.

Even when one of De Angelis’ umbrella companies was caught shorting a $70 million contract in food-grade oil to Third World countries—with vegetable oil cans that literally leaked across the globe—he denied responsibility and suggested the cans were stored improperly in overseas warehouses.

The steady stream of lawsuits and fines were accepted by De Angelis as the cost of business. They were the price he happily paid to rule over a vast, wealth-generating ocean of soybean oil housed at the storage center on his Bayonne tank farm.

De Angelis was chasing almost unimaginable wealth and his secret was inside the tanks. What the feds forgot; what the irate Midwest grain princes missed; and what the banks didn’t realize: Oil floats on water.

Buck-Wild Bedlam

De Angelis needed a whale. He needed big money to play a big, rigged game.

The Bayonne tank farm was his collateral cash-cow to obtain operating loans through a field warehousing system. To get loans from a given bank, De Angelis used independent authenticators to visit the tank farm and verify the presence of a given amount of vegetable oil. The verification receipts were handed to the bank as a form of tinder: The receipts weren’t currency, but they were close.

However, De Angelis wanted a major player with financial gravitas to take his scheme to a grand level, and he found an easy mark in American Express. AmEx had expanded beyond credit cards and travelers checks, and kicked off American Express Field Warehousing, designed to make money using product inventory as collateral. The fledgling company initially was an albatross for its parent, AmEx—until an ill-fated meeting with De Angelis.

With American Express Field Warehousing facing a threat of closure, De Angelis wined and dined Donald Miller, an AmEx rep, and showed him the vast expanse of the Bayonne tank farm. Miller saw Allied’s vegetable oil tanks; Miller believed. A deal was struck and De Angelis had his whale.

Allied turned AmEx-verified warehouse receipts into loans from 51 big-time institutions, including Procter & Gamble, Chase Manhattan, Bank of America, and Bank Leumi. In turn, AmEx got a cut of each transaction. However, none of the 51 counting houses noticed that De Angelis’ reported oil holdings exceeded USDA’s entire national inventory level.

Backed by the stalwart reputation of AmEx, De Angelis accelerated the con. In total, AmEx wrote Allied receipts for almost 1 billion lb. of soybean and cottonseed oil, and De Angelis accessed cash by the bucketload. In a sense, the Bayonne tank farm printed its own money.

With the pieces of the con in place, De Angelis steered the most stunning ag commodity scam in history. How? The ocean of vegetable oil contained in Allied’s Bayonne tank farm was a mirage. De Angelis filled tanks with 40’ of seawater, topped by 2’ of vegetable oil; placed metal columns filled with vegetable oil inside empty tanks to trick inspectors; transferred oil from tank to tank with a secret pump system; demanded 24-hour notice before inspections; forged receipts; listed non-existent tanks in the Allied ledger; and double-certified tanks that other companies had already inventoried.

It was deception on a colossal level. Rumors and whispers surrounded De Angelis’ operation, but the accusations consistently failed to gain traction. When a tipster contacted Donald Miller and insisted Allied’s Bayonne tanks were filled with seawater, an inspection was conducted, but the tank farm passed with flying colors and AmEx got back in the groove signing receipts.

In full flimflam mode, De Angelis’s greed was unbounded. Enough was never enough. Instead, he turned up the volume and rocked the financial world to its foundations.

Open the Books

Moving from strength to strength in 1961, De Angelis scored a big sale when Spain bought 275 million lb. of oil for $36.5 million. Yet, at that moment, De Angelis didn’t have enough oil on hand to cover the long-term order. What to do? He purchased soybean oil futures. However, once De Angelis walked onto the futures high dive, Spain backed out. Adios.

De Angelis was trapped in a vise. Sell below cost and get back a portion? Sit tight? Instead, he doubled down and bought on the margin, intending to swallow supply, jack prices, and sell at the crest of the wave. By 1962, Allied accounted for a whopping 75% of U.S. exports in vegetable oil, shipping 361 million lb.

Even when prices stalled and export predictions dipped, De Angelis maintained full thrust, using dummy companies to bloody the water and keep soybean oil on a high. After the USSR’s sunflower crop failed in 1963, De Angelis bought more, convinced the Soviet Union and its customers soon would need his oil.

De Angelis lured Wall Street investing firms into his soybean web by floating his AmEx connections. Initially, he was rejected by Merrill Lynch, but Ira Haupt & Co. and Williston & Beane gave him their ear and jumped into soybean speculation, igniting a frenzy of buying.

It was mad money: “By mid-1963, he (De Angelis) had contracted to buy 20,000 tank cars of oil—an astonishing 1.2 billion lb., worth about $120 million,” noted Time magazine in 1965. “With every 10-cent shift in price, he stood to gain or lose $12 million.”

During a six-week span in autumn 1963, soybean oil prices rose from $9.20 to $10.30 per pound, and De Angelis believed he was in the clear. But on Nov. 15, all hell broke loose at Allied: The U.S. Senate stopped negotiations on wheat exports to the USSR, and the market got nervy with projections that soybean and cottonseed oil were next in line.

The same day, Nov. 15, a USDA inspector from the Commodity Exchange Authority walked into De Angelis’ office with a pointed request: “Open the Books.”

A wild selloff ensued, and De Angelis’ phone line jammed with scores of calls from bewildered bankers, confused investors, and outraged brokers. The numbers were damning: In 48 hours, soybean oil tumbled to $7.60 per pound and all eyes were on Allied.

Lifting the Lid

Despite Allied’s certain path to bankruptcy, complete panic was kept at bay. After all, most players involved had AmEx receipts—proof of collateral. Although logistically tangled, the solution was simple: Split Allied’s oil amongst the new owners according to the receipts.

But how to divvy phantom oil?

Bunge Limited, one of Allied’s big exporters, sent an inspection team to the tank farm to claim $15 million in oil. The Bunge inspectors found their company’s four designated tanks, opened the lids, and discovered three empties and a fourth only half-full.

“Allied was the cheapest seller, and therefore we were tempted into the cheapest source of supply,” Bunge President Walter Klein said of the prolonged hoodwink.

When Bunge asked AmEx for an explanation, the dominoes began to fall. Behind Bunge, other companies conducted on-site inspections and the truth spilled: Most of the containers at Allied’s Bayonne tank farm were empty or filled with saltwater and sludge.

Tricked repeatedly by De Angelis, AmEx was a pushover and its “inspections” of Allied’s tanks bordered on comedy. As noted by Time: “De Angelis' men duped Amexco with surprising ease. Often, one of them would clamber to the top of a tank, drop in a weighted tape measure, then shout down to an Amexco inspector on the ground that the tank was 90% full.”

Of the purported 1.8 billion lb. of oil holdings in Allied’s books, the tank farm only held 110 million lb., i.e., De Angelis was a complete charlatan.

For most companies caught in Allied’s salad oil swindle, the losses were irretrievable: “No one told us to stop dealing with De Angelis, but I wish they had,” said Charles Sabin, of Continental Grain Co. “We dealt with him with our eyes wide open, but I guess they weren’t open wide enough.”

The Commodities Exchange Authority swiftly announced an official investigation of Allied. De Angelis filed for bankruptcy on Nov. 19, 1963, and public news of the salad oil scandal broke on Nov. 20. Ira Haupt & Co. and Williston & Beane were suspended from NYSE trading, leaving thousands of clients in a lurch. Piling on the surreal nature of Allied’s collapse, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated on the afternoon of Nov. 22, shutting down the NYSE until the following Tuesday, Nov. 26. On the hook for $35 million ($342M at current rates), Ira Haupt & Co. was liquidated, and Williston & Beane was forced into a merger.

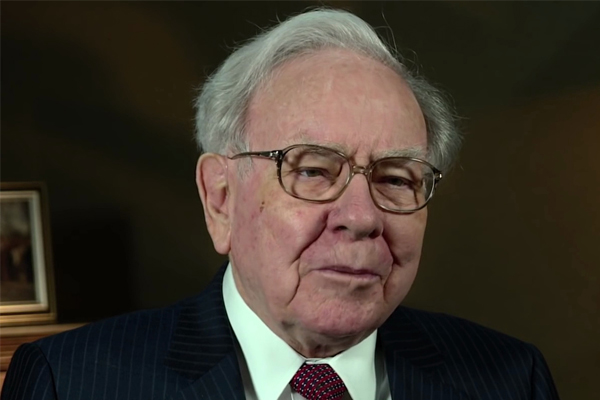

Exit the Salad Oil King; Enter Warren Buffet.

Bunking with Jimmy

According to Wall Street consensus, AmEx was dying or dead, and faced a 50% stock price drop and $210 million in lawsuits due to its field warehousing subsidiary. (Allied’s fall sent American Express Field Warehousing into bankruptcy and caused the failure of 20 more companies and $200 million in losses, not counting stock market losses.)

Hearing predictions of AmEx’s demise, a relatively unknown Omaha investor, Warren Buffet, 33, quietly watched from the periphery. Convinced that AmEx’s substructure was solid, Buffet shook off all naysayers and dropped a third of his investment group’s capital into AmEx at bargain prices. Buffet snagged 5% of AmEx for $20 million. In less than a decade his stake’s value increased tenfold and became a significant factor in his ascent to the heights of global finance.

As for De Angelis, he blamed USDA (“They called me a guinea bastard down there,”) and Midwest agriculture (“Powerful forces were working against me,”). De Angelis insisted 16 of the largest Midwest grain dealers colluded in the creation of Vegetable Oil Export Co. to thwart his business. Despite his claims, De Angelis pled guilty to conspiracy and fraud, and was sentenced in 1965 to 20 years in Lewisburg Penitentiary. Adding color to an already bizarre dynamic, De Angelis was housed for several years in a cell beside Jimmy Hoffa—serving 58 months for jury tampering.

After seven years, De Angelis, 56, was paroled in 1972, and announced his days outside the law were over: “I did wrong and I paid the penalty. I have friends all over the world who would be glad to help me rehabilitate myself.”

But once beyond the walls of Lewisburg, De Angelis sprinted back to agriculture theft.

Hong Kong Sardine Dodge

De Angelis returned to the profession of his youth, meatpacking. Brazenly, he set up Rex Pork, Inc., in North Bergen, N.J., across the Hudson River from Manhattan.

In 1975, USDA filed a complaint against Rex Pork, accusing the company of failing to make payment for $3.5 million in hogs. De Angelis was indignant: “Everybody’s going for a Pulitzer Prize. Who’s the easiest fellow to pick on—somebody who’s been in jail. It’s like Nixon. A fellow gets in trouble and everybody lays on him.”

The Des Moines Register telephoned De Angelis for comment and received a stiff response. “I don’t care what you put in your paper, but if you ever publish anything about me and it’s untrue, I’ll cut your ******* throat from ear to ear,” De Angelis told the Register. “You can record this. I did 15 years in prison, and nobody’s ever going to hurt me again.”

Via umbrella companies—Rex Pork, Miller Pork Packers, Harwell Industries, Hamilton Dean Inc., Porkmasters Inc., Prize Protein Pigs, Meadow Meats—De Angelis bought large quantities of livestock, but repeatedly refused to pay. (He took M&R Livestock in Indianapolis for $3.5 million.)

Once again, the feds prosecuted De Angelis and he pled guilty in a $7 million livestock swindle. He was sentenced in 1980 to seven years in the pen. In 1983, De Angelis was paroled.

Wash, rinse, repeat. He resurfaced in 1984 as general manager of Enfield’s Natural Lean Pork Co., in NYC. By the early 1990s, De Angelis was deep in another con, using forged letters of credit from the Savings Bank of the Finger Lakes to buy pork. In 1993, De Angelis, 77, pled guilty to interstate transportation of fraudulent securities and admitted bilking a Canadian firm (Fearman’s Fresh Meats in Ontario) out of $1 million. Another prison sentence and another parole for an old dog that never lost his bite.

De Angelis’ lifetime of ill-gotten gains apparently suited his health: He died in 2009 at 93—no doubt taking many secrets to the grave, including hidden account numbers.

From the high to the mighty, De Angelis fooled them all. Hyperbole aside, his soybean scam is historically monumental. As recapped by Time: “So climaxed the latest chapter in the continuing, incredible soybean scandal—the most prodigious swindle in modern times … Sixteen companies have been bankrupted. Eleven firms controlled by De Angelis have gone under, as have two respected Wall Street brokerage houses and one subsidiary of American Express Co. Embarrassed bankers from London to San Francisco have been taken for many millions. So have De Angelis' customers, notably the Isbrandtsen Shipping Line, and such worldwide commodities dealers as Continental Grain Co. and the Bunge Corp.”

In the shadow of NYC—where the world’s sharpest financiers held court, De Angelis used soybeans to pull off a nuclear version of the classic Hong Kong sardine dodge, described by Norman Miller in the April 1964 issue of Saturday Evening Post. “During a famine in China, a Hong Kong merchant sold a sardine can filled with mud to another merchant, who sold it at a profit to a third merchant who sold it at a profit to a fourth. When merchant No. 5 discovered the fraud and complained, No. 4 had a comeback: ‘Why did you open the can?’”

Sixty years after the Salad Oil scandal, the enormity of the scheme remains breathtaking. All said, De Angelis likely engineered the theft of over $1 billion when factored at current rates. The ultimate summation is left to De Angelis: “From 1948-1963, I was the largest exporter of vegetable oil and animal fats from the United States. I was the Salad Oil King. I had 32 plants. The government acknowledges I did 68% of all exports year after year.”

Sincerely. Agriculture’s con artist crown rightfully belongs to King Anthony “Tino” De Angelis.

To read more stories from Chris Bennett (cbennett@farmjournal.com 662-592-1106) see:

Priceless Pistol Found After Decades Lost in Farmhouse Attic

Judas Goats: Agriculture’s Bizarre, Drug-Addicted Masters of Deceit Once Ruled the Killing Floor

Cottonmouth Farmer: The Insane Tale of a Buck-Wild Scheme to Corner the Snake Venom Market

Tractorcade: How an Epic Convoy and Legendary Farmer Army Shook Washington, D.C.

Bagging the Tomato King: The Insane Hunt for Agriculture’s Wildest Con Man

Young Farmer uses YouTube and Video Games to Buy $1.8M Land

While America Slept, China Stole the Farm

Bizarre Mystery of Mummified Coon Dog Solved After 40 Years

The Arrowhead whisperer: Stunning Indian Artifact Collection Found on Farmland

Fleecing the Farm: How a Fake Crop Fueled a Bizarre $25 Million Ag Scam

Skeleton In the Walls: Mysterious Arkansas Farmhouse Hides Civil War History

US Farming Loses the King of Combines

Ghost in the House: A Forgotten American Farming Tragedy

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Evil Grain: The Wild Tale of History’s Biggest Crop Insurance Scam