Farmland Detective Finds Grave of Youngest Civil War Soldier?

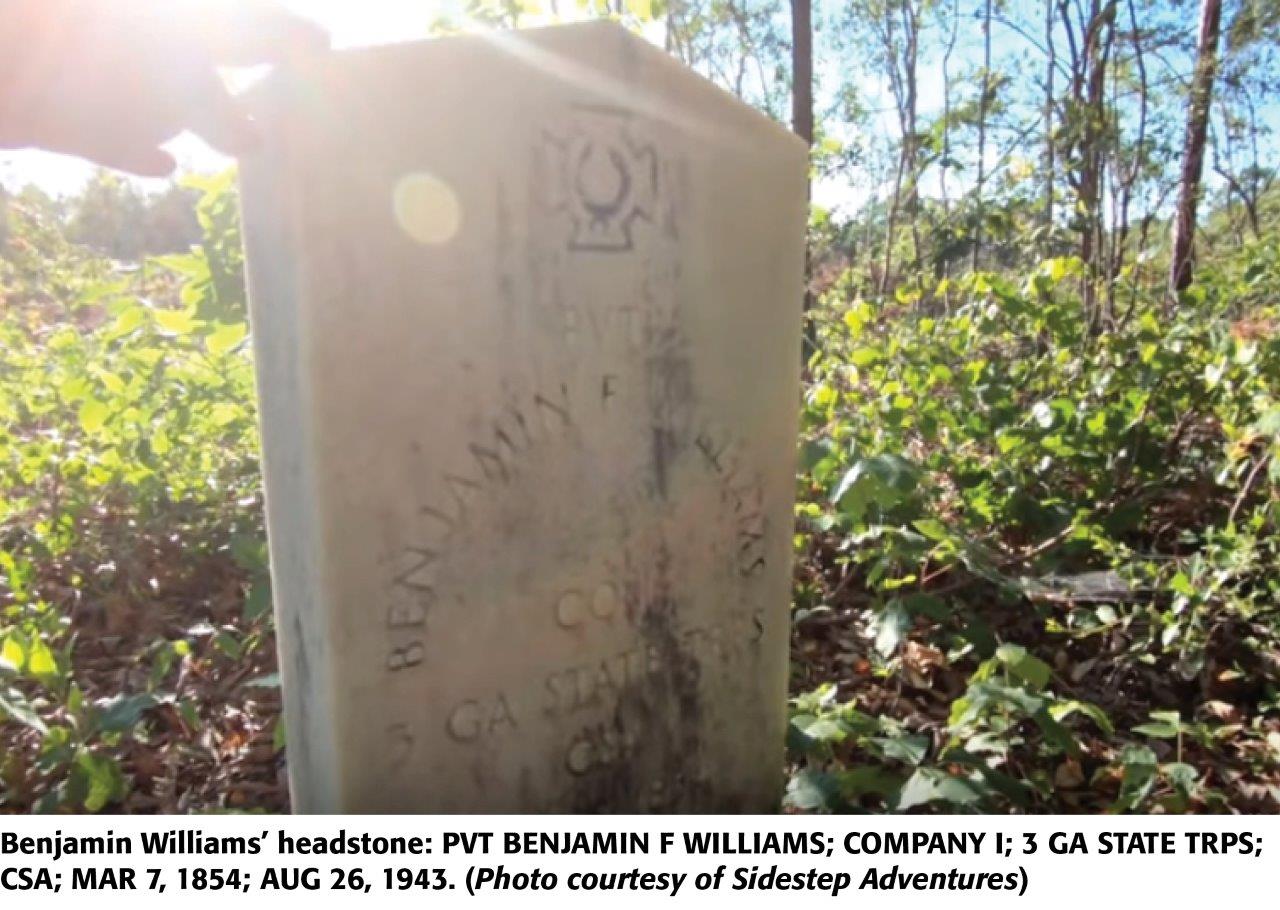

Kneeling in the fallen leaves of a backroad family cemetery at the edge of forgotten farmland in the bowels of Stewart County, Georgia, Robert Wright ran his fingers along the edges of an inscription in white marble, and stared in bewilderment at a tombstone almost hidden from memory. The marker denoted 1854 as the birthdate of Private Benjamin F. Williams, and the gravity of the moment sat heavy on Wright’s shoulders: He had stumbled over the grave of possibly the youngest soldier to serve in the Civil War.

Farmland is the grand repository of America’s past, but the secrets within are rapidly disappearing. The dirt of a mere 40 acres in Georgia, Iowa, Mississippi, Ohio, or any other state often contains the chronicles and lifetimes of countless families or events lost to history, evidenced by the decrepit remains of a farmhouse, graveyard, odd patch of old-growth timber, a rise in the land where a sharecropper shack once stood, or even an old ditch filled with rusting detritus and crushed glass—the hallmarks of hardscrabble existence. As the memories grow ever fainter, Wright, an insatiable hunter of history, is intent on capturing the echoes. “Everything out there leads right back to agrarian society in some way,” he says, “and it’s vanishing before our eyes.”

Sidestep Adventures

Wright, a son of Waverly Hall, Ga., is a proud link in a distant chain of poor dirt farmers. Raised in the extreme west of the Peach State in Harris and Marion counties, Wright spent a childhood tracing red clay roads with uncles and cousins, searching for the remnants of family lore. His mother, an amateur genealogist, carried the young Wright to countless tiny cemeteries in search of obscure relatives lost in the backwoods. As an adult, Wright gravitated toward photography, and was drawn in by old sites with a hint of history. Whether a barn faded by the sun to seven shades of gray, or a rickety house with its accompanying farm fields long since swallowed by a tangle of trees, Wright was game to capture the memory on camera.

In 2015, while searching for photography haunts, he chanced upon a sharecropper house once hidden by pines, but exposed after a massive clear-cut. Wright made a mental note of the location and drove on, intending to return and capture the house on camera. Several days too late, he visited the spot once more and found a blank: The clear-cut scrub had been burned and the house consumed by fire. In place for at least 100 years, the shotgun shack had emerged from hiding for a handful of days and then disappeared forever.

Wright was nauseous over the loss. “Gone in an instant and what a waste. I could have taken pictures, but I missed a moment in time and it’ll never come back. That became a big driver for me to find, document and photograph these types of places because history is very quickly fading away.”

The lost sharecropper home triggered on online urgency in Wright and helped launch a rollicking YouTube channel, all in an attempt to record and document history inexorably tied by a tangle of strings to agriculture. Sidestep Adventures, launched by Wright and several friends in 2017, is a chronicle of in-the-field searches, with a rapidly expanding audience receiving a steady dose of farmland, homesteads, abandoned mills, ghost towns, and graveyards. “My uncle, and friend, Brian Mallard, was big into video, and I asked him to follow me and film some of these sites, and that’s how Sidestep Adventures was born. Our goal is to document it before it’s gone,” Wright emphasizes.

“Most everything I find and film is related down the line to farming. Think back to all the spots and sites your grandparents or old relatives knew about. They were aware of so many places, but in just the span of a few years, much of that is gone. I can’t even tell you how many times I find an open field or dense woods, and I’m told, ‘That’s where the so-and-so farm was located.’ But it’s not there now and maybe only gone in the last 20 years.”

Intent on beating the clock and making a record of old sites, Wright never presumed Sidestep Adventures would rack up several million views and 60,000-plus subscribers. He maintains a drumbeat of historically rich discoveries, none more so than young Benjamin Williams’ boy-to-man leap from farm to Civil War battlefield.

Beacons of Marble

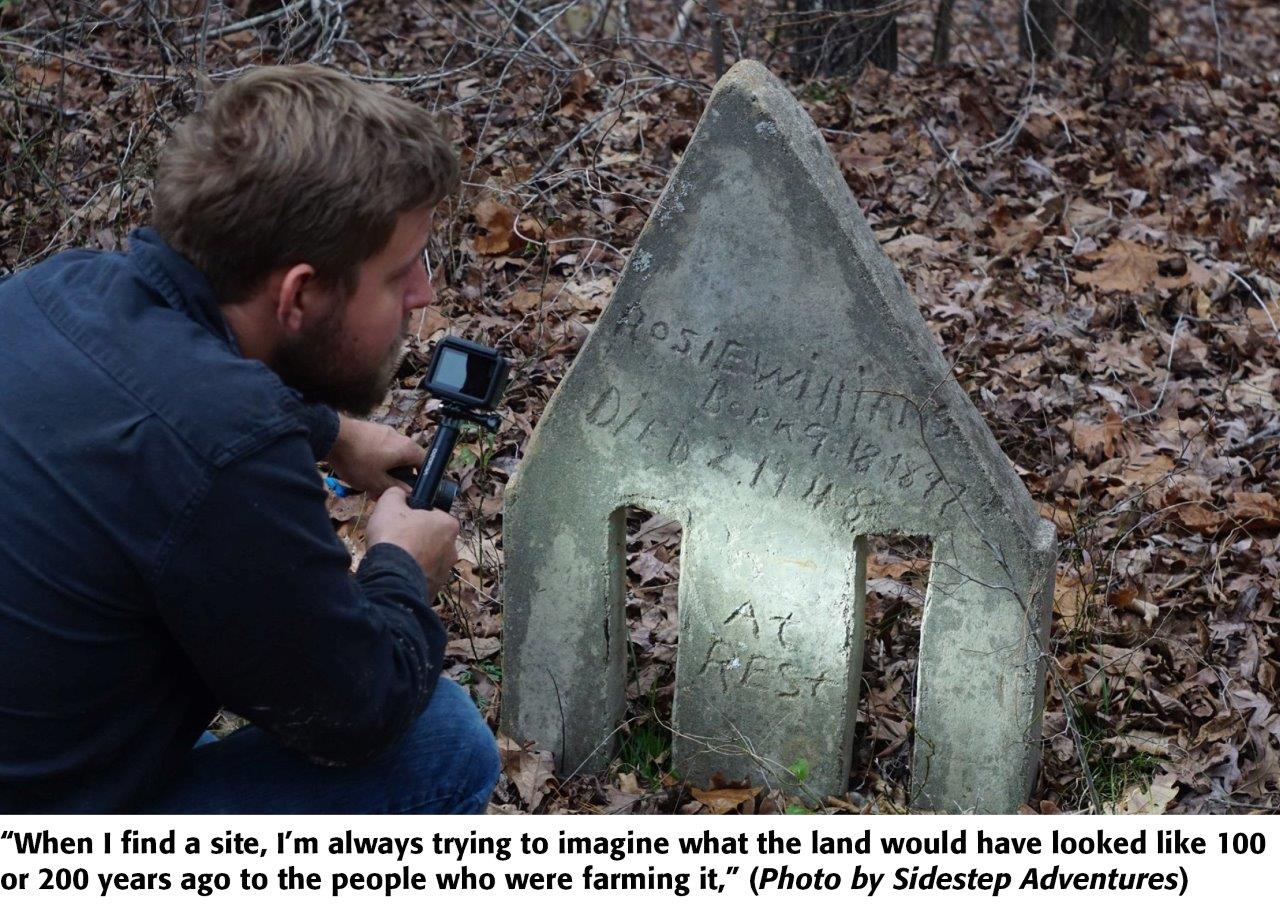

When a house and its farm structures are gone and accompanying farmland replaced by stretches of trees, the landscape often bears almost no trace of yesteryear. Before a farm history fades into its final chapter, time lingers longest on the last page—the family cemetery and a motley collection of gravestones. Whether local field rock, sandstone, marble, granite, or concrete, each stone is a story—a last testament. “When I find a site, I’m always trying to imagine what the land would have looked like 100 or 200 years ago to the people who were farming it,” Wright says. “If they could get up out of their graves and look around, they wouldn’t recognize their own land because everything familiar is gone. Even a whole plantation might be swallowed up, with nothing there to point to it except an old oak tree and a handful of headstones.”

“These are people just like you and me with lives, names, families, losses, triumphs and tragedies, yet covered by the trees and neglected by time,” he adds.

In March 2020, Wright received an email regarding a cemetery deep in the woods of Stewart County. Specifically, the tipoff mentioned three cemeteries in close proximity on a particular backroad filled with washouts and mud holes. With only crude directions, Wright set out in his requisite Jeep Grand Cherokee and began rolling down red clay, eyes peeled for a gentle rise in the land, telltale hardwood, a trace of human habitation—any sliver of incongruity contrasted with endless, new-growth trees.

Hope dimming an hour into the search, and the late afternoon sun dropping behind the vehicle, he slowed at a fork in the road and peered down the right arm, at a sandy drive lined with the haggard undergrowth of a recent clear-cut, and caught the glint of a white reflection. “It was a miracle. At first, I actually thought the shine was a road sign in the distance,” he recalls.

Hardly. Wright’s eyes, aided by the angled slant of the sun, were zeroed on beacons of marble—a pair of upright headstones with pointed tops, a clear distinction of Confederate grave markers.

Answers—and more Questions

The inscription on the first headstone rocked Wright: PVT BENJAMIN F WILLIAMS; COMPANY I; 3 GA STATE TRPS; CSA; MAR 7, 1854; AUG 26, 1943. “I spent so long staring at the words and dates. I knew very young boys served on both sides during the Civil War, but Benjamin Williams’ age made my head spin. He would have been 7 when the war started in 1861 and 11 when it ended in 1865. It is unimaginable in today’s sensibilities and it was hard to wrap my mind around.”

Directly adjacent, the second headstone also bore a jarring surprise. It was the marker of a Confederate officer—and father of Benjamin Williams: CAPT NATHANIEL J WILLIAMS; CO 1; GA STATE TRPS; CSA; JAN 8, 1816; AUG 23, 1894. (Both headstones fronted slabs, and parallel to the graves, third from the right, was a third slab, with no headstone, marking the burial of Benjamin Williams’ mother: LOUISE A WILLIAMS; MAR 3, 1827; JUNE 24, 1913.)

On its face, military service by children in the Civil War wasn’t unusual for the South or North. Drummers, color bearers, powder boys, and a variety of other roles were filled by young boys, but Williams’ age of service, potentially at 7 years old, was highly exceptional. According to most historical consensus, the youngest child to serve as a Union soldier was Edward Black (born May 30, 1853), who joined the 21st Indiana Volunteers on July 24, 1861—at 8 years old. David Bailey Freeman (born May 1, 1851) is often cited as the youngest Confederate soldier and he joined the 6th Georgia Cavalry at age 11. (Charles Hay is also on record as an 11-year-old Confederate soldier from Alabama.)

“I can’t state this as historical record and I haven’t been able to document this, but I’m told by a local historian that Williams served at 7 years old as a wagon driver in a supply chain,” Wright says.

If Wright’s assessment is correct, Williams would have commanded a team of two to six horses, carrying food, ammunition and wounded soldiers, along with a wide array of general supplies. Significantly, the young boy’s wagon/livestock skills likely would have been garnered directly on the farm. “He would have learned everything he knew on the farm,” Wright explains. “It didn’t matter your age, everyone had to play a role on the land.”

“The Williams cemetery matches with most of the family graveyards I find,” Wright continues. “It’s only a stone’s throw from where the house and farmland were located. Sometimes these graveyards were only 50’ from the back porch of the main dwelling, and other times they were on an isolated spot on the farm.”

Williams died in 1943, age 89, in Atlanta, and was laid to rest in Stewart County. As an octogenarian who survived the Civil War, Williams witnessed the Indian Wars, Spanish-American War, World War l and the outbreak of World War ll—an astonishing span of conflicts.

“Every time I stand in one of these cemeteries, or find one of these old farms, I realize I’m just barely scratching the surface. It’s impossible to even begin to measure all the lost history,” Wright says.

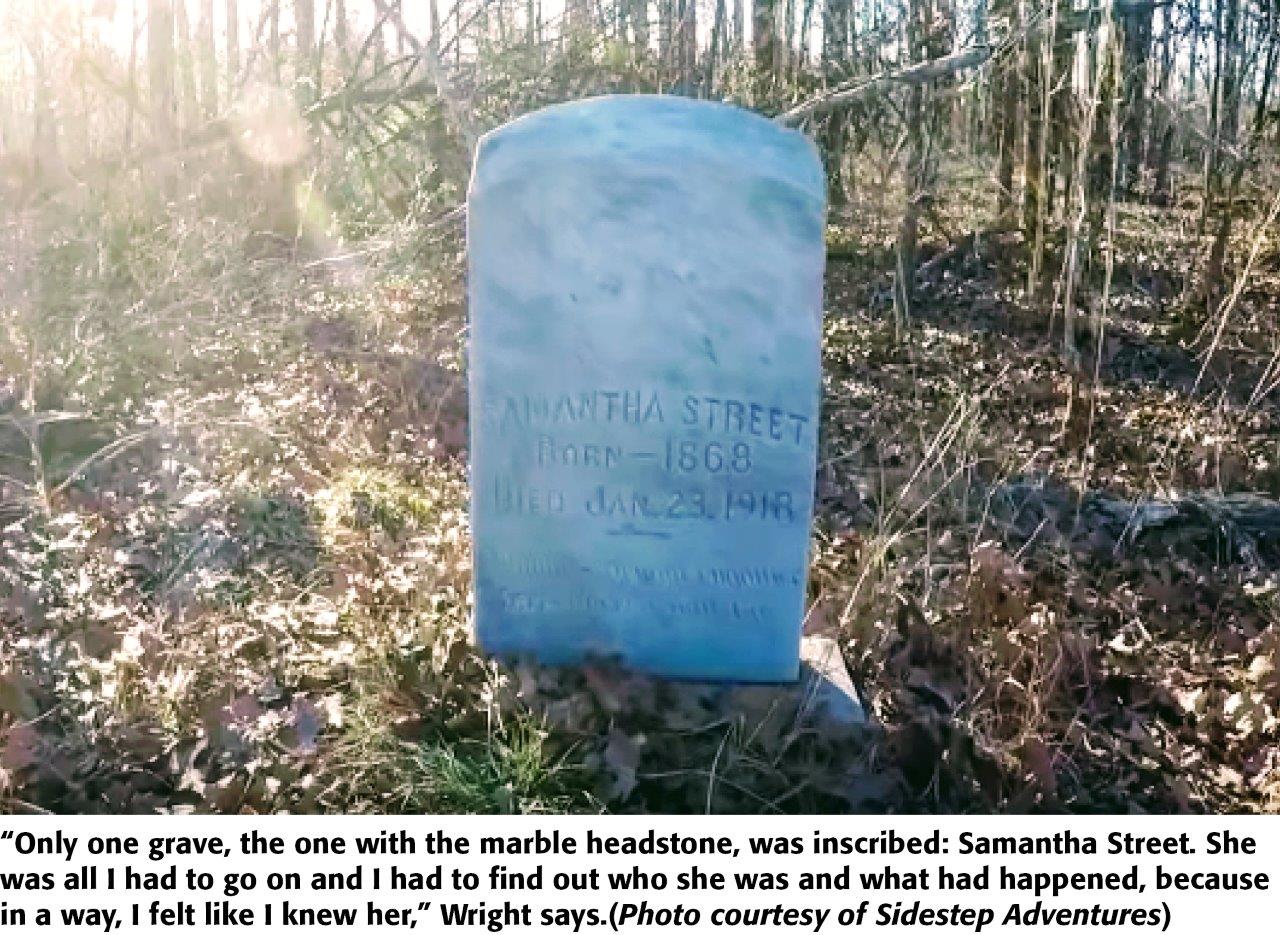

Indeed. Finding an extreme rarity such as the gravesite of a child-soldier stirs up more questions than answers, and such was a similar case in 2018, when Wright came across a long-forgotten slave cemetery—and the poignant tale of Samantha Street.

Samantha’s Voice

In 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, Georgia held roughly 462,000 slaves. One hundred and twenty years later, the gravesites of the vast majority are entirely lost. However, Wright keeps a keen eye out for potential slave cemeteries, and his diligence has paid off on multiple occasions, none more memorable than his introduction to Samantha Street.

“I’ve grown a special appreciation for finding slave cemeteries because you’re often looking at graves that tell you almost nothing. It’s surreal to stand in the woods surrounded by hundreds of graves with no inscribed markers, only flat stones instead, and those are often broken or lost or stolen.”

The slave cemeteries encountered by Wright are often hidden at a wooded corner adjacent to a crop field, or lost in plain sight just off a country road. The cemeteries remained in use after the Civil War, with former slaves and their descendants often choosing burial at the sites. “You can still find stones with names from the 20th century in the mix,” Wright describes, “but those usually tail off in the 1930s.”

As an adult, Wright was drawn back to a childhood memory on a Harris County road he had often traveled. Each fall, as the curtain of foliage fell, he looked off the road and into an odd patch of woods, and saw a single, mysterious white marker. In 2018, Wright found the site, and only 20’ off the blacktop, marveled at the shock of locating far more than a marble headstone. The upright marker was inscribed with the name of Samantha Street, 1868-1918— and served as a sentinel for a host of slave graves. Just feet beyond the white stone, the ground was littered with sunken indentations and crude gravestones of all type, shape and condition—maybe 100 plots in total.

“At first, I didn’t know what I was looking at, but the unmarked graves were scattered everywhere,” Wright describes. “Only one grave, the one with the marble headstone, was inscribed: Samantha Street. She was all I had to go on and I had to find out who she was and what had happened, because in a way, I felt like I knew her.”

Wright began searching for answers and found a key source of explanation in local historian Dan Akin. “Dan has been an absolute incredible resource for history in the Talbot and Harris county areas. He is absolutely amazing, and the knowledge he has in his head is absolutely astonishing,” Wright says. “He can take me to any site, or lost cemetery in the woods, and fill in so much information that otherwise would be lost to time.”

Right out of the gate, Akin explained that Street had been born a slave; the stone’s 1868 birthdate was incorrect. Street’s true birthdate may have never been recorded, and the chronology of her life was a jumble of errors. Akin explains: “Samantha Whitehead (Street) was born into slavery on the William Whitehead plantation, just a few hundred yards from where she rests today. After freedom and beginning in 1870, she gave a different age on every census, probably because she did not know for certain, nor could she read or write. On the 1900 census she gave her date of birth as Dec. 1825, her age as 74, and had been married 20 years. In 1910 she gave her age as 66 and had been married 40 years.”

According to Akin, Street (probably in her later teens) was given by William Whitehead to his daughter, Catherine Whitehead Boddie. Following the Civil War and freedom, Street married in 1867. She and her husband, Hilliard Street (porter and custodian at the I. H. Pitts & Son mercantile, cotton gin and warehouses), lived at the Boddie farm, and Street began working as a nanny for the children of Catherine Whitehead Boddie’s niece, Mary Jane Whitehead Pitts.

Akin continues: “One of those children was William I. H. Pitts. When he married and had children, ‘Aunt Samanthee,’ as she was called by them, became nanny to his daughter, Miss Margaret Pitts. When Samantha died, Miss Margaret Pitts was 24. Miss Margaret told me many times that she paid the delivery and setting fee for the grave marker as well as one for Hilliard, who is buried beside his wife, but his grave marker disappeared long ago.” (Pitts died in 1998; age 104.)

Trimmed down, Street wanted to be buried with her people, and Pitts, who loved and revered the woman who had raised her, paid for the tombstone that still stands today. “Just think,” Wright emphasizes, “if Samantha Street wasn’t buried in that cemetery, we’d never know it was there and it’d be lost forever. Everybody in there has a similar story, but Samantha speaks for all of them.”

Yesterday’s Mysteries

While the intrepid Wright continues to find decaying shacks, abandoned cemeteries and forgotten farms, his frustration with public apathy is a constant weight. In the recent past, Wright consistently contacted county officials after making significant finds—including old cemeteries on the verge of destruction, but he met with muted response. “The lack of concern is depressing and I no longer get involved in trying to get city or county officials to preserve locations or put up marker fences, because they almost never, never respond. Instead, I document with my camera and move on to find another place. I have to point out that Stewart County is the exception and they love to preserve their history.”

With each find and discovery, Wright uncovers his own personal family story by proxy. His great-great grandfather, Shady Joyner, originally of Randolph County, moved to Macon County after fighting in the Civil War. In Joyner’s final years, between bouts of clarity and dementia, he incessantly attempted to walk to a local railroad station and board the train back to Randolph County—specific destination within its bounds unknown. “It’s a shame because wherever he was trying to get to is now lost forever. I don’t even know where his farm was in Randolph County and I don’t even know where he grew up. But that’s the same way for most family histories everywhere,” Wright notes. “If someone doesn’t make the effort to preserve the details, everything disappears.”

Full steam ahead, Wright is birddogging the trail of yesterday’s mysteries, releasing Sidestep Adventures videos of his finds at a near weekly rate. “It’s so ironic because when I was a little boy, I’d see pine woods or cemeteries and think these were lonely spots on virgin land, as if nobody had ever lived there. Now I know the truth: Just 100 years ago, in every corner of every area, there were farms and people. Those isolated cemeteries I find today tell the story of a family or farm community that once thrived in that exact spot. That is history worth remembering.”

For more, see:

Government Cameras Hidden on Private Property? Welcome to Open Fields

Descent Into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

A Skeptical Farmer's Monster Message on Profitability

Farmer Refuses to Roll, Rips Lid Off IRS Behavior

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Shattered Taboo: Death of a Farm and Resurrection of a Farmer

Frozen Dinosaur: Farmer Finds Huge Alligator Snapping Turtle Under Ice

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

The Great Shame: Mississippi Delta 2019 Flood of Hell and High Water

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer

Farmer Builds DIY Solution to Stop Grain Bin Deaths

Corn Maverick: Cracking the Mystery of 60-Inch Rows

Blood And Dirt: A Farmer's 30-Year Fight With The Feds