A Skeptical Farmer’s Monster Message on Profitability

Adam Chappell was a slave to pigweed. In 2009, several years prior to the roller coaster rise and fall of commodity prices, he was on the brink of bankruptcy and facing a go broke or go green proposition. Drowning in a whirlpool of input costs, Chappell cut bait from conventional agriculture and dove headfirst into a bootstrap version of innovative farming. Roughly 10 years later, his operation is transformed, and the 41-year-old grower doesn’t mince words: It was all about the money.

How does a farmer pull the handbrake on an agronomic system, toss pride out the window, and start again? Ask Chappell. Maverick, contrarian, skeptic, trailblazer, or pragmatist, the tags fit Chappell to a T. Blessed and cursed with a manic mind in constant motion, he conducts a symphony of wide rows, public varieties, low planting populations, non-GMO production, cover crops, livestock, intercropping, and more—all with a keen eye fixed on savings. “Money fuels my engine,” he says. “Call it soil health, conservation, sustainable, regenerative, or any other buzzword of the day—frankly, I don’t care. My savings have been incredible and I just call my farming what it is: survival and profitability.”

YouTube Lifeline

Four generations of Chappells have farmed ground in northeast Arkansas’s Woodruff County, just outside the tiny town of Cotton Plant—80 miles west of the Mississippi River. On 8,000 acres, riding a sandy ridge between the Cache River and Bayou Deview bottoms, Chappell and his brother, Seth, 39, grow corn, cotton, rice, soybeans and a mix of small grains.

In 2009, Chappell was neck-deep in Palmer amaranth, fighting a weed plague, and noting the gradual inefficacy of herbicides. Woodruff County, a ground zero location for Palmer amaranth armed to the teeth with multiple modes of resistance, spawned pigweed packed with hellish genetics. “We were fighting an uphill battle and spending so much money on chemicals, but I didn’t know what else to do.”

Each season, prior to spring, Chappell began burndown in February and followed a pattern common among Mid-South growers: a mix of glyphosate, 2-4D, dicamba, and a residual in hopes of staying clean until planting. Next, he’d bed up, and almost without fail, get a 3” or 4” soaker and watch as a flush of pigweed jumped from the ground—depending on the muscle of the residual. In response, Chappell re-bed to bury pigweed seeds, or sprayed gramoxone depending on bed condition. It was clockwork frustration, and the Palmer parasite sucked cash straight from Chappell’s pocket.

Once a crop was in, the pigweed melee was back to full-bore. Cotton, for example, got Reflex two weeks prior to the planter, and then gramoxone and Direx behind the planter, followed by shots of glyphosate and Dual. In a final stab, Chappell rolled with hooded sprayers for a direct application of MSMA and Caparol. And each year, the patient pigweed came back, stronger than ever and ready to claim more ground. “It was bam, bam, bam, on herbicide inputs. The answer floated by the big companies was more and more chemicals, and meanwhile we were steadily going broke,” he recalls.

Chappell began looking for help in the early fall of 2009, a lifeline to relieve heavy chemical costs, but he was essentially a man on an island. Where to turn? YouTube.

Body Blows

Watching endless videos on organic production, Chappell stumbled over an upload from a Pennsylvania pumpkin grower planting no till into tall, green grass—6’ cereal rye. Significantly, the field was clean. No weeds. A few more weeks of research later, Chappell rolled the dice and planted all he could afford—300 acres of cereal rye. The following spring, pigweed control was substantial, and Chappell didn’t till and didn’t need any burndown work on the 300 acres, but he jumped on the rye, hesitant to let it grow over 1’ tall: “We were scared to plant into it and kept it short that first year, which we don’t do now. Everybody told us if you let it stay green, you’ll have cutworms and armyworms, but I’ve since found out that what you’re told and what is reality are two different things.”

In the moment, even for a farmer with degrees in botany and entomology, Chappell didn’t care about science or soil health; all that mattered was a major Palmer decline. “I wasn’t worried about why or how because I could see with my own eyes that pigweed was few and far between. They weren’t nonexistent, but the ones that did get loose, we could walk out there and pull them up. No chopping crew and no chemicals necessary.”

The next season, Chappell planted 1,300 acres of covers, followed by 2,300 acres in 2011. Despite his optimism, Chappell’s operation was about to undergo four years of body blows. Both Chappell’s father, Dewayne, and Seth, lost homes to heavy flooding in 2011, and severe drought took a toll on operations across the Mid-South in 2012. In late 2013, commodity prices began a rapid decline, and in 2014, the Chappells were skinned by Turner Grain in one of the most infamous agribusiness scandals of the modern farming era.

Yet, in the middle of the turmoil, particularly in the 2012 drought, Chappell noted marked differences on cover crop ground planted with multiple grass and legume species, far beyond weed control. “Our crops under covers were so much better, even better than no till or conventional ground. It wasn’t a big yield bump in my corn and soybeans on covers, but it was the money spent to get those yields. And in cotton, the cover difference was in irrigating once every 10 days and making 1,200 lb. per acre, instead of irrigating twice a week and making 1,000 lb. per acre.”

“That was when a light bulb truly came on in my head. We started making room in the budget, prioritizing cover planting in the fall, and covering every acre when possible. Cover crops were no longer optional—they had to be on every acre. No doubt, if we hadn’t changed our way of farming, we’d have been out of business. In my opinion, farming has become a convenience-first enterprise, and not a profit-first enterprise. So many of the things I see in farming that make no sense really come down to convenience.”

Cover crop seed, combined with planting costs, runs $15-$20 per acre on Chappell’s operation, a significant cost across thousands of acres. However, the expense is a bargain, he contends, compared with the dollars he once spent on fall tillage, fall-applied herbicides, winter burndown, spring tillage and bed preparation.

What about time? Has Chappell’s cover crop scheme created a time crunch? Rather, the hours saved from ground rigs and airplanes, and putting out burndown ahead of rain, have provided Chappell with even more latitude, he explains: “I’d say I have more time in spring than most guys in conventional farming. They put out chemicals every chance until spring, and bed everything up. My stuff stays parked until April, and then we go plant and spray behind the planter.”

The Skeptic

Covers are only one facet of change in Chappell’s approach to farming. He hasn’t put out phosphorus and potassium in granular form since 2016, and doesn’t rely on soil samples for fertility recommendations, but instead uses the samples to gauge soil level changes. “We used to take soil tests and find very high levels or optimal levels of a particular nutrient, yet I’d get a recommendation to put that exact one out. That seems silly to me, but most people take it at face value and do it. I’m skeptical by nature and when somebody tells me to do something, I wanna know why.”

“I was told we’d mine the soil out, but I’m finding out that’s not true,” he continues. “Out of all the ground we cut P and K on since 2016, the levels haven’t moved and in some cases they’ve gone up. We’re cycling nutrients from deeper in the profile and bringing them up. The savings on P and K alone are really big.”

In 2019, Chappell brought in 40 head of cattle to feed off covers, upped the number to 70 in 2020, and intends to build the herd. In addition, he added sheep to the livestock mix in early 2020: “We’re gonna increase livestock and add on fence like we did with covers. People think fencing is a huge expense, but it’s not when you’re talking T-posts and single-strand hotwire.”

Chappell grows wheat and hairy vetch together, separates the seeds via a cleaner, and comes back with the vetch as part of his cover crop mix. “Vetch sells for maybe $1.20 and most guys try to kill it out of wheat, but I’m taking advantage. That’s two products off the same acre, and vetch is providing my wheat with nitrogen.”

Relay cropping may be next in the fall of 2020. Chappell has waited three years for a decent weather window, and hopes to plant twin-row 38” wheat with a full season soybean in the middles. Essentially, he would harvest the wheat, aiming for 40 bu., and then let the soybeans fill in the gaps. “Think about profit potential. If you make a half crop of wheat, maybe 40 bu., but you make a soybean on top, look at the added value per acre. If you can get $6 for your wheat, you just added $240 per acre on top of your soy.”

Eye to the markets, Chappell tries to watch for new crop potential, and believes sunflower and its intercropping potential would do well on his ground, but Woodruff County is far removed from any sunflower delivery points. Conversely, canola has made a few inroads on several farms in Arkansas and the Mid-South, but Chappell is keeping his powder dry. “I’ve got to wait on canola. ADM has pushed canola as a possibility down here, but crops have to be able to tolerate wet feet in my area and I’ve got to learn more about how it does down here.”

Not afraid to swing and miss, Chappell’s cropping formula is in steady flux, with ongoing trials of particular crops. As a cover crop addition, he recently tried phacelia, a plant loved by pollinators with deep roots almost capable of filling a 5-gallon bucket. On paper, phacelia was perfect; in reality, it was an ill-fit in the heat of Woodruff County. “I got some phacelia seed and it did terrible. It’s a beautiful plant, but it didn’t work and it wasn’t cheap. Alright then, I tried and learned.”

Non-GMO crops make up 90% of Chappell’s grain acreage, and he leans heavily on the low cost of public varieties and the potential for saving seed. “Non-GMO is all about profitability. Take a public soybean like UA5014 that yields so well and can be saved. The next year, the only costs you’ve got are whatever the market value of the soybean seed is and getting it custom cleaned. If beans are $9, you might be looking at $12-13. Meanwhile, what does an Extend bean cost? Maybe $75? On the backside, you can get $1-2 above Chicago for that bushel of non-GMO beans, but if you’re growing a GMO, you take them to the river and get Chicago minus the basis.”

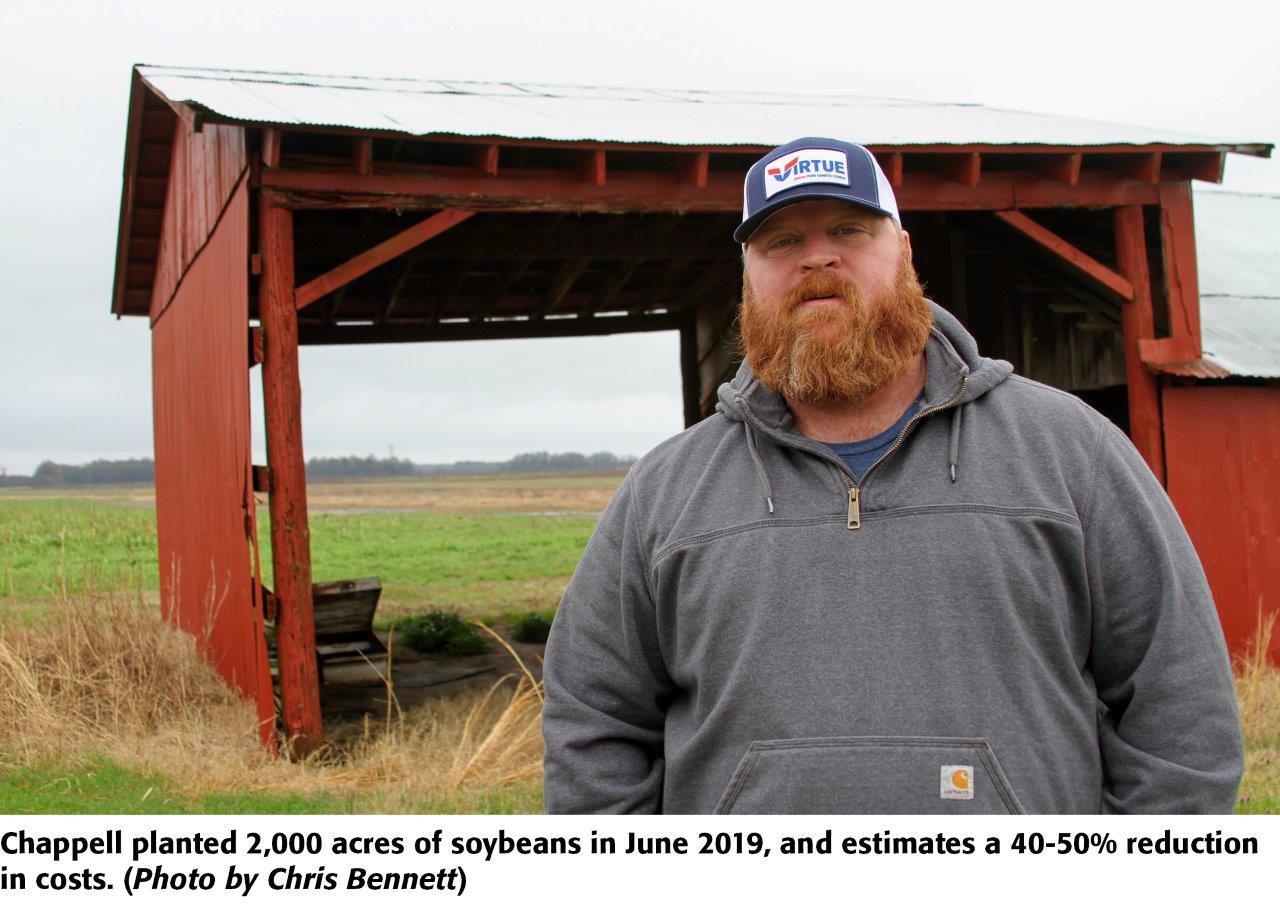

Chappell planted 2,000 acres of soybeans in June 2019, and estimates a 40-50% reduction in costs. Seed expense of public conventional varieties and self-treatment was $12 per acre. After minimal insect treatments and weed sprays, he managed to hit yields in the mid-60s, and gained a non-GMO bonus of $1-$2 over Chicago.

He insists non-GMO crops will return significant yield. “In many cases, seed companies don’t want you to know the same corn hybrid you buy in a triple stack is available as a non-GMO seed. That’s two-thirds to half the money starting out of the gate—huge savings, plus a premium on the backside for non-GMO corn and soy. Why people don’t want to do that baffles me. Save money, get similar yield, grab a premium.”

Wide Rows/Seed Population

When he talks about crop management, Chappell spills out ideas in machine-gun style, overflowing with a passion he can’t contain. Agronomics is deeply layered with questions and conjecture, and Chappell is intent on digging through the strata, allowing his brain to crank on crop management, often to the point of obsession. A sleeping pill or a shot of whiskey, sometimes Chappell has to keep his gears from grinding all night, but still ends up pillow researching seeding rates on an iPad. “I get excited and can’t get enough, and it tortures me trying to fall asleep. I’ll be up in the middle of the night just trying to get my thoughts to slow down.”

Chappell is highly dubious about conventional seeding rates, and he is trialing wide 76” cotton rows and says the format may become permanent. “I made good cotton in 2019 even though I planted late, and it’s half the seed costs off the bat, and the only fertility was 300 lb. of ammonium sulfate, or 63 units of nitrogen. If some of the Australians are planting 15,000 to 20,000 seeds per acre and getting tremendous yields, why are some of us planting 40,000 per acre?”

The proverbial old county fair cotton plant, raised with plenty of space and laden with an outrageous amount of bolls, is constantly on Chappell’s mind. More space brings more fruit, as well as less water and seed. But does the theory apply to practice? “I may put all my cotton in 76” rows from now on. There’s also no humidity deep in the canopy and you can avoid target spot and boll rot. Plus, I’m seeing gains in picker efficiency of 15%. This is not just about cotton, but extends to any crop.”

Chappell had profitable cotton across his farm in 2019, but one particular 40-acre field, planted in 76” rows, showed noteworthy returns. Planted late into a cover mat on May 28, Chappell recorded nearly 100% emergence on a 20,000 seeding rate. At a cost of $585 per bag of seed, the 20,000 seeding rate cost $51 per acre, as opposed to the typical $102 per acre he spends when seeding at a 40,000 rate. (Chappell intends to drop the rate to 16,000 in 2020.) In addition, Chappell treated his own seed at a cost of $5 per acre—imidacloprid and a food source for microbes.

Again, he hasn’t applied potassium or phosphorus to his soil since 2016. However, Chappell did add 300 lb. per acre of AMS one month prior to planting at $52 per acre, and later dropped an in furrow treatment of micronutrients at $16 per acre. Regarding weeds, he spent $38 per acre on a herbicide program, plus sprayer operation costs. As for plant bugs, Chappell made a remarkably low number of sprays during the season—1.5 with imidacloprid at $3 per acre.

All told, the field yielded 1,097 lb. per acre at 74 cents per pound—$812 per acre. Prior to fixed costs and overhead, the margin was a stellar $586 per acre.

Even with Chappell’s excitement over the cotton numbers, hybrid rice is his next big push. “Look at hybrid rice seed and all the data pointing at yields of fields planted at 10 pounds to the acre, but they’re telling us to plant 22 pounds. Why? I can make the same yields at 10? I saw a guy this year that had 1 hybrid rice plant per square foot and the seed company told him to keep that stand. Work that backwards and that’s about 3 pounds of seed per acre. The company said to keep it? That tells me we’re planting way too much damned seed. There’s more money to be made right there.”

“How Far Can I Go?”

Over the past several years, Chappell’s crop management has drawn increasing questions from fellow farmers in the South and well beyond, but attempting to extract added value from each acre is an approach Chappell says is steadily increasing in agriculture, and he credits other growers with many of his innovations. “There are some really sharp fellas in my own state like Robby Bevis, Keith Scoggins, the Carwell family and Mikey Taylor. Or look up in Iowa at Loran Steinlage, or Jason Mauck in Indiana. These guys all have one thing in common: They try to find a way to get every bit of profit off every inch of their land.”

Bevis, 42, a fifth-generation producer, grows 1,700 acres of corn, rice and soybeans in Lonoke, Ark., approximately 30 miles east of Little Rock, and began a major farm transformation in 2012, with a no till and cover crop combination. Weather permitting, he attempts to put all his acreage in covers each fall. Bevis’ “best ground is still his best ground,” but input costs have drastically fallen across his entire operation. In addition, prior to covers his toughest soybean ground typically hit 50 bpa dryland yields, and dropped to 10 bpa during drought years. However, the same ground is now more forgiving, only dropping to 40 bpa during drought years.

“Don’t take 40 acres on your backside, maybe your worst field that’s never produced, put it into no till, and expect production in a year. But we can take that worst field, apply all the soil health tools in the box together, and make the field produce.”

Bevis shares Chappell’s passion, and says the Cotton Plant producer is unique in his willingness to wade into deep water. “Adam is not afraid to break the mold and he’ll push the envelope to extremes. Try 10 acres and see what happens? No, he’ll try 100. So many guys won’t come out of their box, but nobody told Adam he’s even got a box. Row rice, true wide row cotton and so much else, he is a true pioneer and innovator. Then again, some of his innovation is going back to basics because we’ve all overthought farming.”

Bevis stays fired up over soil health, but says margin per acre reigns supreme: “Reality says money drives me and Adam, and all of us. I’m not gonna keep doing what my papaw did and go broke. No sir and no thanks. I’m gonna focus on margin per acre, be profitable, and continue farming.”

Roughly 75 miles northwest of Bevis, and 60 miles directly north of Chappell, Keith Scoggins farms 700 acres of corn, rice and soybeans in Newport, and is in the process of moving all of his ground to no till and covers. Scoggins, 41, wears a hat beyond farming, as Arkansas’ state cropland agronomist for NRCS: “My whole deal is knowing how holistic management works and I’m never going to walk in and tell somebody how things work from a manual or classroom. Credibility is everything and I tell them how it works on my own farm.”

Scoggins speak bluntly, and says long-term, he doesn’t see conventional farming as profitable on many operations. “We’re a dying breed as farmers, and part of the reason is that lots of guys can go into other occupations and make more money. When you look back at the past 30 years and see commodities tanking while equipment costs jump 400%, you better find a difference maker because genetics and yield bumps are not cutting it. What young guys don’t realize is that farming is not just about this year; it’s about being profitable for the next 30 to 40 years.”

Scoggins advocates for growers to take 40 to 80 acres and split the field down the middle, one side in covers for multiple years. “Keep close track of all inputs and let the field pencil out the truth. There are so many guys out there right now in tight spots that won’t take a risk on a small piece of land. They don’t see short-term gains and therefore won’t go for it. Everybody talks big in February meetings, but when it comes late July, and we’re getting combines ready to get corn out, most guys don’t care anymore and get too busy to consider covers or real changes in their farming system.”

Echoing Bevis, Scoggins says Chappell is an uncommon producer: “Adam has tried so many things before anyone else, like a real pioneer. He’s thrown pride away, embraced hard reality, and used holistic management to get a grip. Now he’s pushing and pushing, trying to find out just how far he can go. I know that’s what Adam is thinking: ‘How far can I go?’”

Crazy on the Block

Along with Bevis (current ASHA president), Taylor and Scoggins, Chappell played a major role in founding the Arkansas Soil Health Alliance (ASHA) in 2016, a non-profit closely allied with NRCS and University or Arkansas Extension. “I see more and more guys coming to our meetings, and more guys asking questions,” Chappell notes. “I’m there to learn too, and I get to find out so much from what other guys are trying.”

Chappell’s frank nature and willingness to consider all options has made him an in-demand speaker on the farm meeting circuit during winter months across the U.S. “I’m the one that’s supposed to do all the talking, but you can bet I’m listening and learning, trying to soak in everything from guys in other states. No farmer, and I don’t care who you are, can afford to be complacent and stop learning.”

With the fire in his belly always burning hotter, what does tomorrow look like for a grower marching to a unique drumbeat? “I’m just geared this way, and I don’t mind being the crazy person on the block, because I don’t pay anyone’s bills but mine,” Chappell concludes. “Why would I care about growing 240-bushel corn for 10 bushels of profit? How in the hell is that better than 200-bushel corn with a 40-bushel profit? Money drives me, and one thing for sure, convenience and farming are not a combination that means more money.”

For more, see:

Descent Into Hell: Farmer Escapes Corn Tomb Death

Farmer Refuses to Roll, Rips Lid Off IRS Behavior

Rat Hunting with the Dogs of War, Farming's Greatest Show on Legs

Killing Hogzilla: Hunting a Monster Wild Pig

Shattered Taboo: Death of a Farm and Resurrection of a Farmer

Frozen Dinosaur: Farmer Finds Huge Alligator Snapping Turtle Under Ice

Breaking Bad: Chasing the Wildest Con Artist in Farming History

The Great Shame: Mississippi Delta 2019 Flood of Hell and High Water

In the Blood: Hunting Deer Antlers with a Legendary Shed Whisperer

Farmer Builds DIY Solution to Stop Grain Bin Deaths

Corn Maverick: Cracking the Mystery of 60-Inch Rows

Blood And Dirt: A Farmer's 30-Year Fight With The Feds